Invasives and indigenous: Changing patterns of plant growth on the hills of the Knysna Basin

Leaf creep: Why is there so little vegetation on the hillsides in old pictures of Knysna?

Martin Hatchuel investigates

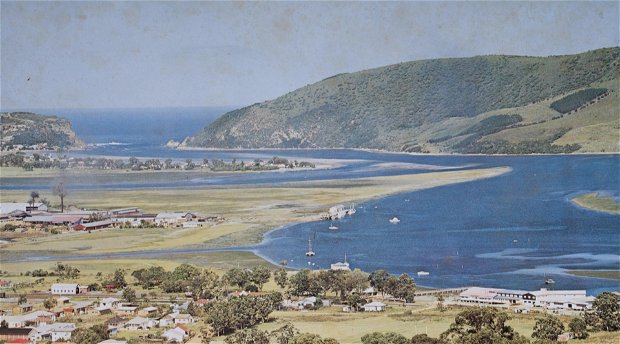

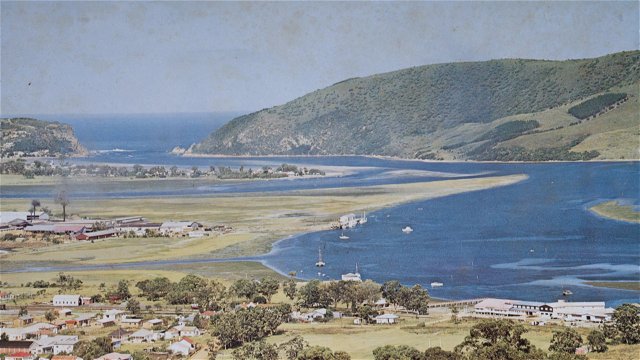

Compare any old image of Knysna, and particularly any old image of the Brenton Peninsula - from, say, the early 1900s - with what you see today, and the contrast is clear: there was far less vegetation on the western banks of the Knysna Lagoon in those days than there is today.

Why is this?

The answer lies both in the ecology of the coastal environment, and in the history of forestry and conservation in South Africa.

Longshore Drift and the Brenton Peninsula

The rocks underlying the Brenton Peninsula are folded Peninsula Formation quartzites of the Table Mountain Group. Overlying this basement, distinctive reddish-yellow Enon conglomerates of the Uitenhage Group occur along the western shore of the Knysna Lagoon, mostly between Belvidere and the area opposite Leisure Isle. These conglomerates are easily recognisable: look for rounded pebbles embedded in the soft rock exposed in cuttings on the road above the Belvidere Pass. (For a detailed discussion, please see, Geology of the Knysna Basin on knysnamuseums.co.za - and refer particularly to Figures B and C. The Enon conglomerates are shown in orange in Figure B.)

The basement rocks of the Brenton Peninsula are covered by a thin veneer of wind-blown sand that was deposited during low sea level, drier climate periods of the Pleistocene glacial epochs. These coastal dunes were repeatedly stabilised by changes in vegetation during brief wet and warm interglacial periods.

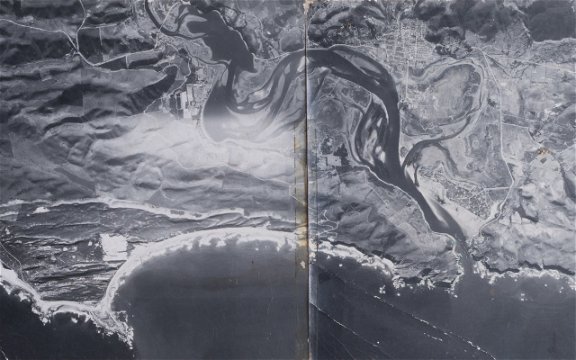

The movement of beach sand onto and over the Peninsula begins with a phenomenon known as longshore drift.

The Southern Cape coast is characterised by a series of rocky promontories similar to the Brenton Peninsula that punctuate the eastern tips of half-heart bays like Buffalo Bay, between Knysna and the Goukamma (‘half-heart bays’ because of their characteristic shape).

Within these bays, longshore drift occurs when the waves carry sand and gravel from the sea at an angle up the beach, and the mix of sand and water then washes straight back down again. This means that individual particles are basically moved along, westwards or eastwards, in a zig-zag pattern.

But, of course, not all the sand is returned to the sea, since some of it is deposited - usually at the high water mark, where the strength of the wash is at its lowest, and where the sand is able to fall out of suspension.

This migration can be disrupted by temporary or permanent barriers on the beach. When this happens, the sand tends to build up into spits or dunes along the shore.

Dune fields are subject to constant change: at times when the action of the waves is gentle, a process of accretion can be observed (the sand is washed up onto the beach, the beach grows in size, lower-lying rocks, etc., disappear). At times when the weather is stormy, the beach is eroded and the sand returns to the sea. And when bad weather coincides with extremely high tides, the sea often eats away at unstable and semistable sand lying inland of the high water mark.

But the movement of the sand isn’t only caused by water: when beach sand dries out, it can become light enough to become wind-borne, and can then be carried for considerable distances.

Given the direction of the prevailing winds, this explains how sand comes to be deposited on the higher slopes of the Brenton Peninsula, and (at the opposite end of the bay), on the dune fields at Goukamma.

Over the last 16,000 years, these aeolian (wind-blown) sands have formed three distinct ridges of between 70 and 100 metres in height that run parallel to the coast between Buffalo Bay and Brenton-on-Sea - ridges that you can easily see when you look down across the landscape from the viewpoint on the Brenton road.

So why are those large, unvegetated areas of sand visible at the top of Featherbed Nature Reserve in older photos - but not today?

That sand is, of course, still there. But as to why it’s now hidden by vegetation - well, that’s where the history of forestry and conservation comes into it.

To begin, it’s necessary to look at shore management in the broader context of the Cape as a whole, and also to understand how the successive forestry departments - which would become responsible for drift sands reclamation - became involved.

The Central Roads Board and the Cape Colonial Forestry Department

In the Knysna Museum's articles, Slavery and labour in the Knysna forests in the 19th Century, and, Labour in the Knysna forests under apartheid, we saw that successive colonial administrations were concerned about preserving South Africa’s small areas of indigenous forests almost from the start: van Riebeeck, for example, had issued a number of placaaten - edicts or decrees - to protect the ‘garden, lands and trees’ of the VOC’s outstation at the Cape.

Forest conservation, though, was only finally formalised in the law with the passage of the Forest and Herbage Act of 1859, which aimed to prevent illegal felling. This was followed by the Tree Planting Act of 1876, which encouraged afforestation and allowed forest rangers to draw up to £25 per plantation for the renewal of Crown Forests. Ten years later the Cape Parliament passed the Forest Act of 1888, for “the better protection of forests” - a role for which a Chief Conservator of Forests would be appointed at the time of Union in 1910. Then in the first half of the Twentieth Century, the country enacted the Union Forest Act of 1913 to consolidate and expand its forest policies - and this in turn was replaced by the more comprehensive Forest and Soil Conservation Act of 1941.

It was against this legislative background that the Cape Forestry Department became the organisation that initiated professional forestry in the colony, and thus the agency responsible for the reclamation of sand dunes - a function it took over from the Public Works Department, which had itself inherited the job from the Central Roads Board.

The Central Roads Board was established by the colonial secretary, John Montagu, shortly after his arrival in the Colony in 1843. One of its first projects was the construction of a gravel road over the Cape Flats, from Maitland to Belville.

Since the sand of the area had become unstable due to human activity, and particularly due to damage caused by the trampling of livestock, the board needed to protect the road surface from drift sands, which it tried to achieve by planting avenues of Australian, as well as indigenous trees. (The Australian species - including Acacias, hakeas, and others, were introduced to the Cape by the pharmacist and businessman, Carl Ferdinand Heinrich von Ludwig - known as Baron von Ludwig - who planted them in the private botanical garden he established on his 1.2 ha property in Kloof Street. This would later become the initial source of the seeds used in the reclamation project.)

In 1845, the Roads Board began reclaiming land at outspans along the route across the Cape Flats, using Australian acacias and hakeas, and other species, too. This reclamation was necessary because regular concentrations of cattle at these communal gathering points had caused severe damage to the vegetation, which exacerbated the problem of drift sands, which threatened infrastructure.

Once established, the trees were useful for other purposes, too: they provided firewood for the city’s expanding urban areas, and fuel for the locomotives that powered the trains from Cape Town to Wellington.

Beginning in 1850, though, pines were planted in the White Sands Plantation (which later became known as the Uitvlugt Plantation, and much later the suburb of Pinelands). Four species were chosen for the economic value of their timber: Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis), cluster pine (P. pinaster), Monterey pine or radiata pine ( P. radiata), and stone pine (P. pinea). (Like the Australian acacias and the hakeas, most of the pines are now listed as invasive aliens in the Western Cape.)

Later, the Superintendent of Plantations, Joseph Storr Lister, (next paragraph) began reclamation at Bellville and Kuilsriver on a grand scale - with the aid of Cape Town’s refuse, as well as Australian acacias, and some indigenous tree species. This work was gradually expanded to the drift sands at Milnerton, Table View, and Bloubergstrand, and to the False Bay Coast - where the classical French style of dune reclamation was used (see ‘Forestry, France, and Drift Sands’ below).

In this way, virtually all the drift sands on the Cape Flats were eventually stabilised.

Although the Department of Public Works succeeded the Central Roads Board in 1866, it retained responsibility for all exotic tree plantings, since its job included protection of infrastructure like roads and railway lines. Thus, when Storr Lister was appointed the Colony’s first Superintendent of Plantations in 1875, he found himself working for Public Works rather than the Department of Crown Lands and Forests - which was responsible for the Colony’s indigenous forests, and which would only welcome its first classically trained professional forester when Count Médéric de Vasselot de Régné, took up the post of Superintendent of Woods and Forests in 1889.

Under de Vasselot, a new Forest Department was created that combined the management of exotic plantations with that of indigenous crown forests - which meant that the plantation function was taken away from Public Works.

Forestry, France, and Drift Sands

Like de Vasselot, the early professionals of the Cape Forestry Department - including people like the ground-breaking author of Forestry in South Africa, David Ernest Hutchins, who served as Conservator of Forests for the Western Conservancy from 1892 - received their training at the French National School of Forestry, in the city of Nancy.

In France, the conservation of water, forests, and soil - and the conservation and reclamation of drift sands or sand dunes - were all considered functions of forestry. This can be partly understood since drift sands in Europe are generally colonised by trees like the cluster pine (also known as the maritime pine), which is indigenous to the Continent, and is both a pioneer plant in that region, and the climax species in the succession.

The French process for reclaiming drift sands involved encouraging the formation of littoral or coastal dunes above the high water mark and parallel to the seashore. They harnessed the power of longshore drift by trapping wind-blown sand against palisades (fences) planted in the dunes, and allowed the dunes to build up to desired levels by lifting these palisades as the deposits accumulated.

When the correct height was achieved, the sand was stabilised with marram grass (or European beach grass - Ammophila arenaria), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ammophila_arenaria which prevented it from moving inland, and prepared the ground for the later planting of pine trees.

Having learned this system in France, the Cape Colony’s foresters introduced it to South Africa in the 1880s, but using both marram grass and sea wheat (Thinopyrum distichum), and instead of cluster pines, by planting Australian species - rooikrans (Acacia cyclops), or Port Jackson willow (Acacia saligna) - as well as indigenous species like wax berry (Morella cordifolia).

In the adapted, South African model, the foresters also lessened the movement of sand by cutting branches from trees growing behind (on the landward side of) the dune fields - both from state forest land that was clad with vegetation, and from private land in the vicinity. They then laid these branches on the surface of the driftsand to create physical wind barriers, and often interplanted these windrows with groves of indigenous fynbos plants, or even with scrub forest species like candlewood (Pterocelastrus tricuspidatus) or white milkwood (Sideroxylon inerme).

All of which brings us back to drift sands and longshore drift.

Left to its own devices, the natural cycle of deposition, stabilisation, and the growth of scrub forests or other vegetative communities along sandy shores rests in a stable equilibrium between the dune fields themselves, and the neighbouring stable interior. This equilibrium is partly maintained by the fact that the stability of the dunes (or primary dunes) increases as you go inland due to the increasing density of the vegetation as you move inland.

While the winds in the Southern Cape that blow south-west in winter and south-east in summer do result in a slight nett inland movement of sand, the vegetation inland remains relatively unaffected because the vegetation on the fringe between the two is able to absorb the sand that drifts across it - unless that vegetation has been broached by trampling and grazing of livestock, which upsets the fragile equilibrium.

But when you upset the equilibrium of the vegetation on the fringes of a dunefield, the sand begins moving inland.

The problem, then, is that early foresters in South Africa (in the period before about the 1970s) didn’t have enough knowledge of this ecological balance to know that their attempts at reclamation and stabilisation were actually interfering with the natural cycle, which in turn affected the lands behind the primary dunes.

In the period since pastoral agriculture took hold in the Cape, uncontrolled grazing of cattle and sheep, the fact that livestock tend to trample the vegetation, and the fact that the farmers burned the veld for short-term improvement in the quality of the grazing caused the lands to become increasingly denuded - and with minimum cover, the damage caused by inland migration of beach sand was exacerbated.

Drift Sands, Farmlands, and the Goukamma River Mouth

When the Cape’s coastal farms were formally surveyed in the 19th Century, their boundaries were set, in some cases, at the edges of the dune fields (depending on the width of the dune fields). In other cases, where the dune fields were originally included in the surveys and the farm boundaries were set at the high water mark, those dune fields were later expropriated by the state.

Either way, almost all the dunefields - which most people considered ‘wastelands’ - were eventually designated crown lands, later to be known as crown forest land, and later still, as state forest land.

Over the years, successive administrators of the Union of South Africa, and then the Republic of South Africa, attempted to deal with the questions of erosion, drift sands, and dunefields reclamation in various ways. The most common method was to appoint interdepartmental committees to identify problem areas, and, in the case of drift sands, cordon them off and have them declared forest reserves.

This is how the Buffalo-Bay/Goukamma area - on both sides of the Goukamma River Mouth - became a forest reserve in the 1930s and 1940s, and also why State Forestry initiated an active reclamation project there, using the classic model of laying cut branches on the sand, and sowing both indigenous and exotic plants (and particularly rooikrans) between the windrows.

From the point of view of stabilisation of the drift sands, the project appeared at first to have been a success - no doubt partly because the rooikrans grew quickly and well here thanks to a lack of predators to control their rate of reproduction, and thanks to the abundant, all-year-round rainfall that was then characteristic of the Southern Cape.

One of the aims of stabilisation was to prevent the river mouth from moving - it would previously have drifted from east to west and back again - but as any regular visitor to Buffalo Bay will have seen, the mouth has its own ideas, and Knysna’s municipal engineers have had to resort to increasingly costly measures to stop it from eroding the only access road in its (current) relentless push eastwards.

A Knysna Forester Remembers

Retired forester, Theo Stehle, who worked both in the Southern Cape and in the Eastern Cape from the 1960s into the present century, took up the story in an interview in late 2020:

The Buffalo Bay State Forest remained state land, although it was later transferred to the control of the Cape Province (now the Western Cape Province), and became the Goukamma Nature Reserve in 1990.

In the early days the reserve was basically reclaimed dune sand covered by a dense mass of rooikrans. But in the 1970s, Sue Milton (later Prof. Sue Milton of the Conservation Ecology Department at the University of Stellenbosch) did an ecological study and experiments on the conversion of land infested by rooikrans to indigenous vegetation.

Her results were very effective, and we used it to good effect in the Eastern Cape, too: the principle was to gradually thin out the rooikrans, while establishing indigenous vegetation in the gaps between them.

The beauty of rooikrans and Port Jackson, of course, is that as legumes they host symbiotic bacteria in their roots that convert atmospheric nitrogen into a form that’s available in the soil to other plants. So the rooikrans actually helped establish the fynbos by fertilising the sand.

Just as we did in the Eastern Cape, at Goukamma they felled the dense rooikrans in rows, leaving standing rows in between. The widths of the felled rows, and the distances between the standing rows, were chosen to optimise the cover so that mice and other rodents could prey on the rooikrans seed, and thus limit the chances of regrowth.

They then sowed the indigenous common veld grass or pypgras (Ehrharta villosa) in the gaps - although being one of the pioneers that comes up naturally after felling, I don’t think they needed to artificially establish much of it. But they also sowed and planted various other indigenous species, too.

In our nurseries in the Eastern Cape, we mostly cultivated pioneers like Ehrharta, and also blombos (Metalasia muricata), bitou (Osteospermum moniliferum), and slangbos or silver stoebe (Seriphium plumosum), which is also a feature of inland fynbos, and which we both grew in the nursery, and sowed on the sands by simply picking the branches and scattering the seed onto the sand.

These species are all indigenous to the Southern Cape, too.

How did the Goukamma and the Brenton Peninsula become covered by rooikrans?

Besides the reclamation projects pursued by state foresters up and down the coast, many private landowners also planted rooikrans on the sand dunes, because they regarded drift sands as undesirable.

To compound the problem, rooikrans, which isn’t indigenous to South Africa, had no real enemies in this country to control the number of viable seeds it produced - so it ‘escaped’ and began colonising both the dunes and neighbouring lands with increasing speed.

And that’s possibly what happened to the sand on The Heads: it was stabilised with rooikrans both by human intervention, and by its own devices.

I believe there might have been an unexpected economic motivation for stabilising the sand on the Brenton Peninsula, too: it was probably deemed undesirable to have sand moving into the Lagoon, into the shipping channel, silting it up, and someone might have stabilised it artificially by sowing rooikrans.

- NOTE: Although rooikrans was introduced to the Cape as far back as the 1820s (see ‘Baron von Ludwig’ above), the first biological control agent that acts against is was only introduced to South Africa in 1994: the weevil, Melanterius servulus, which feeds on the flowers and the developing seeds, and which lays its eggs in the seed pods, leaving its larvae to feed on the seeds. Later, a second agent was released, too: the midge Dasineura dielsi, which lays its eggs on the flowers, this causing the plants to produce galls instead of seed pods in which the larvae and pupae can develop. Similar agents have also been introduced to control Port Jackson and other invasive alien plant species. See fynboshub.co.za.

Was there a lot of grazing and burning in Knysna in the past?

There must have been a lot of grazing and there would have been a lot more burning in the Knysna basin in the distant past.

Definitely, there was regular burning throughout the country. It was an accepted agricultural practice: you burned the land before you tilled it, whether for pastures or for wheat, etc. My father had a farm in the Gansbaai area, typical dune strandveld, and there it was a regular practice to annually burn for grazing. And it’s a practice that predates colonialism: the first Portuguese navigators saw so many fires at the Cape that they called it the ‘Land of smoke’ (Terra de fume) long before any settlement began here.

Strandveld is a generic term for the sandy coastal plains where you find a mixture of dune fynbos, woody shrubs, and scrub forest. Dune thatching reed (Thamnocortus fraternus) is one of the indicator species for dune fynbos, and the woody species like white pear (Apodytes dimidiata sbsp. dimidata), guarrie (Euclea racemosa), candlewood, and white milkwood are typical of the scrub forest.

Would this regular burning and grazing have made an enormous difference to the Great Fire of 1869?

“The Great Fire of 1869 burned a swathe from Humansdorp to Riversdale. Large areas of forest and almost all the grasslands of the region were destroyed.” knysnamuseums.co.za

Difficult to answer this, because it’s so difficult to reconstruct the conditions of the veld at that time.

We do know that there were no large stands of invasive alien vegetation in those days, and the veld probably never became moribund through lack of burning like it does today.

There were also no artificial breaks (like wide roads etc.), and no large cultivated lands.

But wasn’t there a lot more fuel on the landscape before 1869?

No, I don’t think so. In fact, I think from the days of the Khoi and the San who burned regularly, the white colonists just continued those practices. There was also no exotic vegetation in the veld. Everything was burned or grazed.

What was the total size of the Knysna Forests before 1869?

That’s a very contentious subject, but we’ve been trying hard to get the message across that the size of the indigenous forest was probably much the same as it is today.

Some of the indigenous forest was of course totally destroyed and converted or transformed, particularly in the George area - although that was probably more scrub forest. But the proper, high forest remains much as it always was.

Ryno Joubert’s work (The distribution of the Southern Cape forests: Historical and current- pdf download, 3.7mb), which included input from people like myself and experts on forest ecology like Coert Geldenhuys and others - is quite reliable on this subject.

My theory is that there was very little forest loss - even with the Great Fire - because forests have a very specialised niche in the landscape: they are relics from prehistoric wetter climates which shrank into refugia that are protected from fire, mainly by topographic features in the landscape.

But, of course, smaller parts of the forests would indeed have been destroyed.

How did the Great Fire of 1869 compare with the Knysna Fires of 2017?

The 1869 fire occurred during a period affected by a both economic depression and extreme drought during which the Southern Cape experienced a full six weeks of berg winds (hot, dry, northerly winds).

This was very different to the 2017 Fire, which happened during a once-off, freak, catastrophic weather event triggered by climate change.

In 1869, smaller fires had burned on and off for a period of six weeks before the main fires hit the Knysna area. This did temporary damage to the mountain forests, but as I’ve said, the mountain forests are actually adapted to fires. They’re characterised by stinkwood (Ocotea bullata) and red alder or rooiels (Cunonia capensis), both of which sprout from stumps after burning: they coppice.

I remember exploring a mountain forest near Goudveld, above Jubilee Creek, with some of my colleagues. It was quite a high forest of coppices - and we could see that all the stinkwood stumps had been charred in the past. Judging by the size of the coppices - they had already grown into large trees - we reconstructed that they were probably from the 1869 fires.

Conclusion: Those disappearing sand dunes

Theo Stehle’s knowledge of the dynamics of dune vegetation coincides exactly with my own experience following the Knysna Fires of June, 2017, when I was employed as a horticulturist to oversee the rehabilitation of the veld atFeatherbed Nature Reserve, on the Western Head of the lagoon mouth.

The fires destroyed more than 90% of the vegetation on the reserve, burning indigenous and alien species alike, especially in areas where rooikrans had been prevalent - although it did leave much of the old-growth indigenous forest (around the restaurant, and in the kloofs above Coffin Bay and Needles Point) largely intact.

The area on the crown of the peninsula that appears as bare sand in old photographs had previously, as we’ve seen, been invaded by rooikrans, which, when I was a young man helping to build the reserve in the 1980s, presented an almost impenetrable thicket.

Having thrived undisturbed for more than 50 years (pictures from the 1960s show very little rooikrans on the northern slopes of the Brenton Peninsula, but it spread quickly after that), this impenetrable thicket would also have been a tinder box of note that would have contributed considerably to the heat and spread of the fires in 2017.

By the time I returned to Featherbed to begin my rehabilitation work in December, 2017, Knysna had experienced intermittent, gentle rains that triggered germination - and both the rooikrans and the indigenous species had begun growing gloriously.

Since the fires had burned almost all the branches of the rooikrans to ash, our job of physically removing the seedlings by hand was relatively uncomplicated (although often very strenuous, given the steep slopes on which we had to work, and given the fact that we often encountered as many as 200,000 seedlings in each of the 900 square metre blocks in which we worked!).

As expected, the rooikrans and the Ehrharta came up almost simultaneously - but what was surprising was the enormous number of other indigenous species that emerged from seeds that must have been lying dormant under the rooikrans for ages: we identified more than 300 of them (see the Featherbed Nature Reserve project oniNaturalist.org).

By removing the competition from the rooikrans, the reserve’s team made it easier for the indigenous plants to thrive - but, having had the rooikrans on the soil for so many years, with the available nitrogen they had introduced, and with the added benefit of all the other chemicals that would have been deposited there by the fire, what was once a patch of barren beach sand quickly became the lush and verdant fynbos you see there today.

Author

This article was written by Martin Hatchuel with the help of Theo Stehle, forester (retd.) and Ferdi van Berkel, geologist (retd). Published 2021.

Select bibliography & reading list

- Beinert, W.: The Rise of Conservation in South Africa - Settlers, Livestock, and the Environment 1770-1950 - Oxford University Press, 2003

- Bennett, B. & Kruger, F.: Forestry + Water Conservation in South Africa: History, Science + Policy - ANU Press, 2015

- Hatchuel, M.: Labour in the Knysna forests under apartheid - Knysna Museum, 2019

- Hatchuel, M.: Slavery and labour in the Knysna forests during the colonial period - Knysna Museum, 2019

- Hatchuel, M.: Pre-colonial people of the Knysna Forests - Knysna Museum, 2020

- Hatchuel, M. & van Berkel, F: Geology of the Knysna Basin - Knysna Museum, 2019

- Joubert, R.: The distribution of the Southern Cape forests: Historical and current Knysna Museum.

Unpublished manuscript - Reekie, W.D.: The Wood from the Trees: Ex Libri ad Historiam Pertinentes Cognoscere - South African Journal of Economic History, Volume 19, Issue: 1-2, September 2004

- Showers, K.B.: Prehistory of Southern African Forestry: From Vegetable Garden to Tree Plantation - Environment and History 16(3):295-322 DOI: 10.3197/096734010X519771, August 2010

- Stehle, T.: Die ontwikkelingsgeskiedenis van waaisandherwinning in Suid-Afrika tot en met 1909 - Seminar ingehandig vir dir graad van B.Sc. (Bosbou) Hons. Mei 1981. Unpublished manuscript

- Stehle, T: Die ekologie van duinplantegrooi langs die Kaapse kus en die gebruik van inheemse plantegrooi vir die beheer van waaisand, met besondere verwysing na die Oos-Kaapse kusgebied - Seminar ingehandig vir die graad van B.Sc. (Bosbou) Hons., September 1981. Unpublished manuscript

Share This Page