Slavery and labour in the Knysna forests in the 19th Century

The history and economy of the Cape of Good Hope under both Dutch and British rule were directly tied to the practice of slavery. To understand the position of labour in Knysna’s timber industry in the 19th Century, therefore, we try to understand conditions in the Cape Colony as a whole.

Was there a history of slavery in the Knysna forests - and what were conditions like for labour after the abolition of slavery in the Cape Colony on 1 January, 1834?

The story of how the timber from the Knysna Forests was exploited in the 19th and early 20th Centuries is well known (see ‘The woodcutters’ and ‘The timber merchants’ on this site), but under what conditions did people of colour find themselves working during the colonial period?

With only one first-hand account written by a slave in South Africa available to us today - ‘The life of Katie Jacobs, a freed slave’ - and only a limited number of works that tell the stories of individual slaves from their own perspective (see Jackie Loos, ‘Echoes of Slavery,’ and also Iziko Museums, ‘Historical sources on slavery’), most of our modern perception of slavery at the Cape was shaped by the memoirs of free people who visited the region.

The writings of the traveller and socialite, Lady Anne Barnard, the Scottish writer and abolitionist, Thomas Pringle, and Captain Robert Perceval, (the first British officer to reach Cape Town during the 1795 Battle of Muizenberg, when the Dutch lost control of the colony to the British for the first time) paint an unbalanced view of the practice and effects of the institution of slavery - both on the slaves themselves, and on their masters.

This imbalance is seen in Perceval, for example, who published his account in 1804, and who, “claims that British intervention had ameliorated the lot of Cape slaves: even ‘the Dutch treated their slaves much more rigorously before the arrival of the English than afterwards.’ Like other English commentators, Perceval is concerned to subsume Cape slavery into a general category of servitude: ‘The domestic slaves at Cape Town live equally happy as our own servants, and only retain the name of slaves’.” (Vos 1990)

In an attempt to balance our current view of slavery at the Cape, therefore - and to clarify our understanding of labour conditions in the aftermath of abolition - this article presents a brief overview of the history, economy, and laws of the Cape Colony as a base from which to infer what life would have been like for black and coloured people in the Knysna area in the 18th and 19th Centuries.

Background: Forestry and the economy of the Cape Colony in the 18th and early 19th Century

The economy of the Cape of Good Hope was controlled in the 17th and 18th Centuries by the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie: VOC), which, following at least a half a century of economic activity in the region (Mellet 2020), had set up a permanent post on the site of the present-day Cape Town Castle in 1652 under the command of Jan van Riebeeck.

In 1795, though, the VOC lost control of the Cape to Britain, whose strategy for its war with France following the French Revolution required control of the sea route to the East, which meant controlling the southern tip of Africa.

Britain’s first occupation lasted only until 1802, when hostilities with France were temporarily suspended under the Treaty of Amiens - but it annexed the region again in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From then on, the economies of Britain and the Cape became deeply intertwined: “To protect the developing economy… Cape wines were given preferential access to the British market until the mid-1820s. Merino sheep were introduced, and intensive sheep farming was initiated in order to supply wool to British textile mills.” (britannica.com)

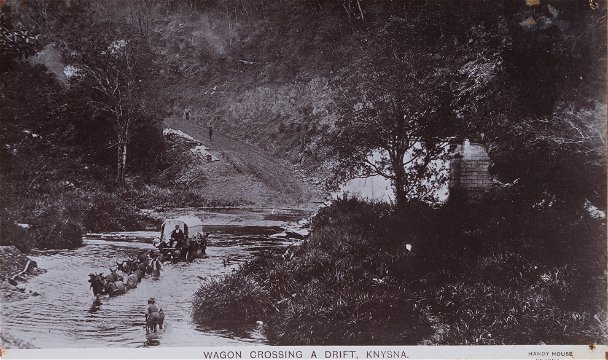

Both Dutch and British administrators of the Cape required a steady supply of timber as raw material for heating and cooking, as a vital component in construction, and in the manufacture of tools, furniture, wagons, and ships.

The Dutch recognised the value of the small amount of forest they found in the vicinity of Cape Town from the start, and did what they could to ensure their protection from logging and external threats - even imposing severe penalties against anyone who deliberately lit grass fires that could spread to and damage the forests: “a second offence of burning without due notice could result in ‘hanging by the cord until death do follow’.” (Reekie 2004)

Nevertheless, the forests near Cape Town were quickly depleted, and an alternate source had to be - and was - found in the Southern Cape. Harbours were therefore established in Mossel Bay in 1786, and in Plettenberg Bay in 1788, although these experiments proved disappointing: in the case of Mossel Bay partly because of the overland distance to the forests (which were situated in the George area), and in Plett, partly because the vagaries of the weather and the tides made the Bay less than ideal as a port.

To add to these economic and resource constraints, the VOC ran the Cape as a monopsony (the Company was the only entity allowed to buy agricultural and other goods - including timber - produced in the territory). This meant that there was little incentive for growth until 1795, when the VOC finally opened up the economy by removing most of its restrictions on internal trade - only to lose control of the territory altogether later in the year...

In 1798, the new colonial government sent James Callander to the Southern Cape to investigate the potential for forestry in the area between Mossel Bay and Algoa Bay.

Callander made the first depth soundings of the Knysna Lagoon - which had been mapped in 1878 by Robert Jacob Gordon - and later showed them to Jonkheer J.W. Janssens, the governor of the Cape during the second Dutch occupation, when Janssens visited the Southern Cape in 1803.

Convinced that the Lagoon was deep enough, and the local forests large enough, Callander tried to make Janssens see Knysna’s great potential both as a harbour, and as a centre for sawmilling and shipbuilding.

Janssens, though, decided that The Heads were impassable for shipping (although this had yet to be tested), and Callander’s proposals came to nothing.

In the following year, though, George Rex - who would later become known as ‘the founder of Knysna’ - sold his property in Cape Town, and bought the farm Melkhoutkraal on the banks of the Knysna River.

Rex had held a lucrative position as marshal of the Vice-Admiralty Court at the Cape - “the maritime equivalent of the sheriff in common-law courts” (van Niekerk 2010) - until that court had been closed down in December, 1802, and “by November 1803 he was ready to take the oath of allegiance to the new Dutch government as all remaining British residents were required to do.” (van Niekerk 2010).

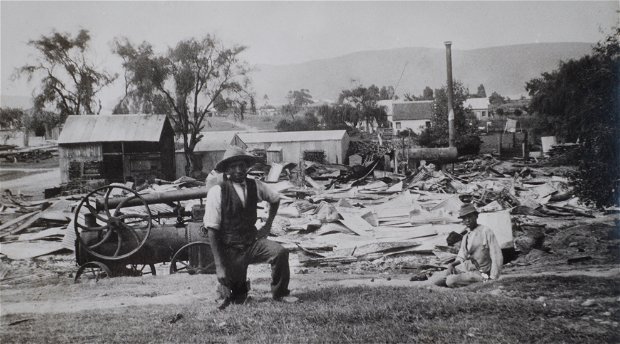

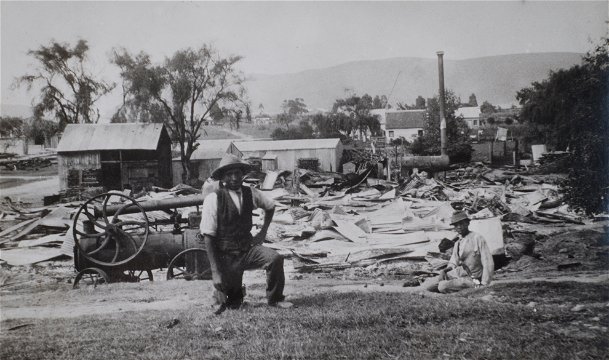

He arrived in the district of Knysna shortly after the end of the Third Xhosa War (1799-1803) to find that the buildings both on Melkhoutkraal and other neighbouring farms had been burned down - although probably not by Xhosa raiding parties, but rather by “a mixed bunch of opportunists, possibly taking advantage of the situation.” (Caveney, P., Knysna Historical Society, personal communication 2020).

Nevertheless, Rex became almost immediately the region’s “major supplier of timber” (Muller 1985), and was soon “engaged in a variety of economic activities, including agriculture, stock-breeding, trading, shipping, and eventually also ship-building. His agricultural activities included the growing of trial crops of flax, hemp, tobacco, and silk. Surplus butter was exported to Cape Town, Algoa Bay, St Helena, and Mauritius. His experiments in animal husbandry included the breeding of horses, cattle, and sheep, merino sheep being imported from Australia to improve the local strain. But his major source of income was from the exportation of timber, felled on his extensive estates or bought from local woodcutters.

“For this latter purpose he opened a trading store at Plettenberg Bay where he bought timber and sold general merchandise. As a merchant he had a virtual monopoly of trade within a radius of 40 kilometres. He also owned various ships.” (Muller 1985)

Slavery in the Cape Colony

The number of known slave wrecks along the coast of South Africa - which date back as far (if not further) than 1550 - shows that slavery cast its shadow over the Cape long before colonialism reached its shores (see ancestors.co.za: Slave shipwrecks on the South African Coast).

According to the Camissa Museum (Mellet/Camissa Museum 2020), the slave trade in the Indian Ocean is estimated to have involved as many as 3.5 million people.

Slavery occurred in this region over three distinct eras:

- The Arabic period, from about 800 to 1500 CE, which was driven by Arabic slave traders based in Zanzibar, Kilwa, Sofala, and Mozambique Island.

- The Portuguese period, which began in about 1490, and was driven by Portuguese traders operating out of Angola, Sofala, and Madagascar; and

- The Colonial period, which was driven by the Dutch, English and French working together with Arabic and Southeast Asian slave traders, and which coincided with the establishment and growth of the refreshment station at the Cape of Good Hope (which later became, of course, the Cape Colony).

Mellet estimates that 63,000 first-generation Africans and Asians were brought to the Cape as slaves between 1652 and 1807, when Britain banned the trade in slaves throughout its possessions (although slavery itself only ended with abolition on 1 January, 1834). On top of the slaves who arrived up to 1807, another 15,000 arrived as ‘prize slaves’ or 'liberated Africans' after the ban (see ‘Emacipation and apprenticeship’ below).

Added to this total of 78,000, a further 30,000 are thought to have died on the high seas en route to Cape Town, bringing the overall number of first generation enslaved at the Cape to almost 110,000.

This total “does not include enslavement as a result of being locally born to enslaved parents.” (Mellet 2020)

The slave population at the Cape grew remarkably quickly, and slaves very soon outnumbered freeburghers altogether.

“Cape slaves were brought to the Colony from Africa and Madagascar (47,300); from India, Sri Lanka, West Bengal, and Bangladesh (17,200), and from Southeast Asia (13,500)” (Mellet 2020) - and also included local Khokhoe cattle herders, who had been forced off their grazing lands in Table Bay by the settlers. (For a discussion on ethnonyms - the naming of ethnic groups - please see ‘Pre-colonial people of the Knysna forests: Footnote’ on this site.)

By 1657 - five years after van Riebeeck set up his refreshment station, and the year in which he allowed the first nine servants of the VOC to go out and farm as freeburghers, and so begin the process of colonisation - ten of the 144 people under VOC rule were enslaved.

Describing the two long journeys of the naturalist and collector François Le Vaillant, who visited the Cape between 1781 and 1784, and published his travelogues in 1790 and 1795, Mutton writes that Le Vaillant encountered four distinct groups of people in the Colony:

- “People of European descent:” officials of the VOC, freeburghers, and “immigrants who settled in and around Cape Town as professionals, traders and farmers”;

- “The indigenous peoples of the Cape area, the Koina and the Sonqua, who lived deep into the Cape hinterland and whom Le Vaillant colloquially referred to as Hottentots and Bushmen. During his journeys, Le Vaillant almost exclusively interacted with the Koina. They were mainly herders who lived in roaming, structured communities all through the Cape area while the Sonqua, hunters and gatherers, lived in more remote areas;”

- The Xhosa, whom Le Vaillant met “living on the outside of the eastern frontier of VOC territory, which was established in 1775 at the Great Fish River. Violations of the arrangement by both the European settlers and the Xhosa led to violent clashes and Border Wars in 1779, 1793 and 1799”; and

- The slaves, “imported as a result of the VOC’s high demand for labor,” who were owned by the VOC as well as by freeburghers in and around Cape Town, and, to a lesser extent, by settlers on farms in the hinterland. (Le Vaillant also reported meeting a small number of freed slaves both in Cape Town and on farms along his route.)

Mutton estimates that , towards the end of the 18th Century, there were about 26,000 slaves in service at the Cape - “both imported and born in slavery” - compared to only about 20,000 freeburghers and around 1,700 freed slaves.

Farmers at the Cape of Good Hope: amongst the worlds wealthiest slave owners

The prevailing thinking during the 20th Century - informed by the historiography of the colonial and Apartheid eras - painted the Cape as both a sleepy economic backwater (which it wasn’t: local slave owners were amongst the wealthiest in the New World (Fourie 2011)), and as a kind of labour utopia in which slaves were treated in a particularly mild or benign manner. (See, for example, Southey, 1992: “A.F. Hattersley believed that while slavery 'did not contribute to the welfare of the settlement', because expenditure by owners on slaves did not yield much financial reward, there was 'little evidence of brutal treatment as a rule;' Eric Walker echoed similar views, arguing that 'take it all round, slavery at the Cape was not cruel;' and J.S, Marais, whose The Cape Coloured people devoted more attention to slavery than any of its predecessors, argued that 'slavery at the Cape was humane -if any form of slavery can be described as humane' and that it 'was free from many of the incidents which tended to brutalise the slaves in other parts of the world'.”)

In fact slavery at the Cape was as insiduous and unbearable an assault on human rights as it was anywhere else in the world: “the entire system of enslavement involved the brutalisation of human beings and is regarded as a crime against humanity.” (Mellet 2020).

While the Colony enjoyed relative prosperity precisely because it operated as a slave-owning economy, the fact of slavery itself mitigated against significant economic growth throughout the 1700s (Fourie 2011).

Although “expropriation of labour without compensation was a fundamental part of the economics of colonialism” (Mellet 2020), the position of the Cape as the midway point for ships sailing between Europe and the Far East, and the Colony’s mild Meditteranean climate - which favoured the production of winter-rainfall crops (and other products such as meat, of course) - ensured considerable material success for the settlers, who were estimated “to have achieved some of the highest levels of per capita wealth in the world.” (Fourie 2011)

Fourie argues that “Cape farmers prospered, on average, because of the economies of scale and scope achieved through slavery. Slaves allowed farmers to specialise in agricultural products that were in high demand from the passing ships - notably, wheat, wine and meat - and the by‐products from these products, such as tallow, skins, soap and candles. In exchange, farmers could import cheap manufactured products from Europe and the East.”

Slaves were thus highly valued - and, since the farmers invested a large share of their surplus earnings in capital goods, it follows that they invested heavily in the purchase of slaves, which constituted as much as one quarter of all their moveable assets.

Probate records from the time (records of the assets in deceased estates) “reveal evidence of an affluent, market-integrated settler society, comparable to the most prosperous regions in eighteenth century England and Holland.” (Fourie 2012)

Fourie selected 28 'products' - including slaves, trousers, cattle, gold rings, and others - “to represent total household wealth” listed in 2,577 probate inventories obtained from the Orphan Chamber at the Cape (which was “established to administer the estates of individuals who died intestate and left heirs either too young or unavailable”).

These 2,577 inventories included a total of 12,682 slaves - an average of 4.92 slaves per household - valued at an average of 126,97 Rixdollars each.

By comparison, the same number of households owned:

- 16,128 horses (6.26 per household at 20,24 Rixdollars each);

- 140,436 cattle (54.5 per household at 9,37 Rixdollars per head);

- 901,357 sheep (349.7 per household, 1,18 Rixdollars each);

- 2,972 guns (1.15 per household at 4,41 Rixdollars per weapon); and

- 3,109 wagons (1.2. per household at 41,38 Rixdollars each).

Emancipation and the apprenticeship system

As we have seen, Britain banned the slave trade in 1807, although it only abolished slavery itself 27 years later when it emancipated all slaves across the Empire in 1834.

The slave owners received financial compensation from the government - a situation that, according to the editor of the Ware Afrikaner writing in 1841, “caused a giddiness in the pockets of the people here similar to the effect produced by strong wine on a head that has been always accustomed to water.” (In Hengherr 1953).

But for the slaves themselves, emancipation wasn’t the end of it, as most of them were indentured to their former owners in an apprenticeship system that ended for one set of former slaves only on 1 August 1838, and for another on 1 August 1840.

Mellet points out, though, that a third group - the 15,000 ‘prize slaves’ or ‘liberated Africans’ who were brought to the Cape after 1807, usually “after being seized by the Royal Navy from slave-trading vessels on the high seas” - were “branded on arrival and forced to undergo a 14-year apprenticeship within 20 miles of Cape Town” (although the period was reduced to five years “after protest in the 1850s”). (Mellet 2020)

The legislative end of slavery, therefore, didN't end slavery’s effects on the people or the economy of the Cape Colony - as we will discuss below (see, ‘Racial and labour legislation in the Cape Colony following emancipation’).

Slavery in the Southern Cape

Many factors - including many of those discussed above - would explain the apparent dearth of wage-earning labourers in the Cape under both the Dutch and the early British occupations (Malan 1993; Fourie 2011), and this sets the background against which we can now briefly look at slavery in the Southern Cape.

An examination of the records of the Registrar of Slaves at George, now held in the Western Cape Archives in Cape Town, indicates a number of slave owners in the George-Knysna area, including, for example, Johannes Ernst Terblans of George, who owned 6 slaves, Johannes Vosloo, also of George, who owned 13 slaves, and George Rex of Knysna, who is listed as having owned a total of 51 slaves - of whom 38 were younger than 13 at the time of registration.

The slave Emilie Lehn

Readers seeking a personal account of slavery in the Southern Cape are reffered to Jackie Loos’ Echoes of Slavery (public library), which recounts, among others, “the recollections of Emilie Lehn (also known as Amiel Leen), whose reminiscences of more than half a lifetime of urban and rural slavery were published in the Christian Express in 1876, when she was in her nineties.”

Loos writes that Johannes Hermanus Terblans, “a Boer from George, who had come with his produce to town, bought me (Ms. Lehn) for £75 and brought me to his farm" in about 1808.

“The Lehns had already lost one son, Hans (b. 1822), who wandered into the forest near George and was never found. According to Emilie, 'a year later a rumour spread that a mad female slave who had fled from her master had stolen and drowned the child in a pool of water, but the truth of this rumour we could not find out ... We slaves had no time to watch our children properly. They were left to themselves, and thus occurred that my little daughter [Steyntjel, one and a half years old, in following other children jumping over a watercourse, missed the other side, fell into the course and was drowned.'

“After living for some years 'partly in peace, partly in sadness,' their master died, and everything had to be sold. In January 1834, after serving five different masters, Emilie was put up for auction.

“‘There I stood with my husband and my two children on the table. The boy must be sold alone, cried out one voice. One bid, another bid, another, the hammer fell, and my son had a master; he must part with us and go far away.’” (Loos 2004)

George Rex, slave owner

- Please see below for a full list of George Rex’s slaves by name - together with notes on their origins and sale - and, by comparison, lists of slaves who belonged to two other slave owners in the region: Johannes Ernst Terblans and Johannes Vosloo.

Although there’s pitifully little information about individual people in the Cape’s slave registers, it is possible to infer the extent of their plight from the information they do contain. Maria, for example, a “female about 6,” who came from Angola was entered as “Housemaid” in Rex’s possession on 20 November, 1818 - but neither of her parents’ names appear in the record.

Similarly, Sanet, 6 (who was registered on 20 November, 1818, and was sold and transferred to G.J. Stroebel of George on 16 December 1830), Herman, 4 (who was registered on 20 November, 1818, and was sold and transferred to H.J. Ungerer of George on 16 December, 1830), Saria, 3, and 2nd Maria, 10 - both registered on 20 November, 1818 - are all listed without reference to any of their parents.

Twenty four of Rex’s slaves were born to women he owned, and therefore automatically became his property. Tereke, for example, produced five children who were registered as slaves: Charles, born 22 March, 1822; Rosina, 20 January, 1824; Kitty, 7 March, 1820; Bel, born 26 July, died 31 July 1831, and Lenera, born 6 February, 1833.

Rex’s slaves also included a girl called Cato, who was born to Sabrina on 18 September, 1833, and who was entered in the slave register on 2 January, 1834 - a day after slavery officially ended in the Colony (the reason for this may have to do with the compensation slave owners received for the emancipation of their ‘property’).

Rex, of course, will have needed many slaves with many different skills in order to enable him to run his considerable estate, and would have had them working in every field from gardening and farming to cutting timber for his export business. But he would also have bought timber from independent woodcutters, and employed local people, “dispossessed of what land they had previously used grazing their cattle” (Storrar 1974) to fulfill his requirements.

While some sources credit Rex with holding as many as 400 licenses for cutting timber, this seems implausible since, according to the Royal Navy’s Captain A.F. Jones, who spent a year investigating the condition of the local forests and published a report of his findings on 1 November, 1812, no system had yet been put in place for the control of cutting in the Southern Cape - a situation he found alarming. (Theal 1908, Hatchuel 1998)

“”Woodcutters pitched up at any place they pleased and commenced with the cutting of trees. The whole extent of the forest in the neighborhood of Plettenberg Bay has been at once made use of, and the consequence is that good timber is getting scarce. A system must be put in place in order to prevent the overuse of the timber resource. To a casual observer there appears to be a great number of trees in every direction, but experienced woodcutters will pass them by as only trees with good and useable timber are felled and used (Phillips 1963).” (Joubert 2019)

How much of the work in the forests was undertaken by slaves is unknown, but since Rex registered only four of his slaves as woodcutters, it’s probably safe to assume that the bulk of his supply came from private contractors who may have been either European (probably Dutch) settlers, or dispossessed Khoe (pastoralists) from the region.

Despite the persistence of felling of quite considerable amounts of timber, “general economic conditions remained depressed,” and by 1823, “woodcutters between George and Knysna were still earning no more than ‘a meagre subsistence’ by taking wagon-loads of timber to Knysna or to Cape Town. [The traveller and writer, George] Thompson remarked [in 1827]: ‘These woodcutters are the poorest class of white people in the Colony; earning a livelihood with severe labour. Unlike [the trader Joseph] Barry at Port Beaufort or [shipping and whaling magnate, John] Murray at Mossel Bay whose activities brought a substantial increase in the welfare of the regions they served, the enterprising Rex appears to have been the main beneficiary of the new [Knysna] harbour, at least during the first years of its existence.” (Muller 1985)

Slavery and the foundations for labour conditions in the 1800s

- “In 1801, ER. Bresler, the new landdrost of Graaff-Reinet, painted a dire picture of relations between masters and 'Hottentot' servants. Servants, he said, viewed their employers 'not as their masters but as their executioners' and served them 'only through hunger and fear.' The settlers had an 'unlimited lust for power'; they regarded it as 'legitimate and inflict it without restraint.' (Dooling 2005)

Although Britain’s Slavery Abolition Bill - which was passed by the House of Commons and the House of Lords in August, 1833 - ended slavery throughout most of the British Empire on 1 August, 1834, and in the Cape on 1 December 1834, the foundations for this abolition - which had been laid years before - laid the foundation for working conditions for decades to come.

In 1809 - at a time when the British people had turned against slavery, and three years after the Cape became a British colony (for the second time) - the governor, Du Pre Alexander, 2nd Earl of Caledon (Lord Caledon), passed his ‘Hottentot Code’ (also known as the Caledon Proclamation, or the Caledon Code), which was designed both to restrict the rights of the KhoeKohoe by enslaving them, and to help settler farmers limit the mobility of the labour force (and which itsef was based on similar, earlier legislation that had been enacted by the Dutch in order to disposess the indigenous people of their land).

According to the Professor Padraig O'Malley, the John Joseph Moakley Distinguished Professor of Peace and Reconciliation, MCCormack Graduate School of Policy Studies, University of Massachusetts Boston, and Visiting Professor of Political Studies at the University of the Western Cape - whose work on South Africa’s transition from Apartheid to Democracy is hosted by the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory, and is accessible at omalley.nelsonmandela.org - while the Proclamation of 1806 purported to outlaw the slave trade, it nevertheless “allowed the settlers to retain and sell or buy their human property.

“... Apparently ... human beings were no longer allowed to be captured and sold as slaves, although it seemingly allowed the ownership and buying/selling of 'human property'.

"The supply of imported labour did not, however, completely stop after 1807; thus, for example, nearly 2,000 'Prize Negroes' were imported into the Colony between 1808 and 1816 and most of them apprenticed to colonists."

The Caledon Code required settlers to register written contracts with any KhoeKhoe who were to be employed for a month or longer, while “the most important article” in the proclamation “stipulated that henceforth all 'Hottentots'” (the pejorative term used for the KhoeKhoe at the time) “were to have a 'fixed place of abode'.” Such “servants” were not allowed to move around without written passes - which only their masters could issuem, and which any white settler could demand “to verify that they were not bound by any contracts. Those in breach of these regulations were classifIed as 'vagrants'.” (Dooling 2005)

The Code “was bolstered by a law passed in 1812 [the Apprenticeship of Servants Act] that made provision for those Khoikhoi children who had been maintained by settlers in their first eight years, to be 'apprenticed' for ten further years.” (Dooling 2005)

Dooling further argues that, “the great significance of the Code was that it sought to limit the personal and arbitrary authority of the master and replace it with the rule of an interventionist colonial state.”

In fact the Code can be seen as the final seal in the process of enslavement of the KhoeKhoe, since it left them with no choice but to work for the settlers or the state - a situation that didn’t go unnoticed: “Dr. John Philip of the London Missionary Society was representative of many when he wrote in his famous Researches in South Africa that the legislation of 1809 consigned 'the Hottentots ... to universal and hopeless slavery’.” (Dooling 2005)

The corruption of authorities in charge of administering the Code placed the KhoeKhoe in a particularly invidious position - despite the fact that it purported to ensure that they would be treated in a fair, torture-free manner by their masters.

In fact, the Code was deeply concerned with regulating violence between masters and servants, which had much to do with the strategic strength of the colony following a KhoeKhoe rebellion that began in 1799, and wasn’t quelled until 1803.

The rebellion stemmed from a period at the end of the 1700s when a number of KhoeKhoe servants joined their masters in putting down disaffected trekboers on the frontier.

“Fearing that they would be forced 'to return to the habitations of their old Oppressors', the Khoikhoi threw in their lot with the Xhosa of the Zuurveld. There was no doubt in the minds of British authori- ties that an alliance of Xhosa and 'Hottentots' threatened the very survival of the Colony.” (Dooling 2005)

Dutch settler support for the new British administration was predicated on being able to retain their property - and especially their slaves, since they rated slaves among their most prized possessions (Martins, 2019).

The Dutch, though, were notably less liberal in their attitudes to the slaves during the first British occupation than during the second. But, having learned their lessons during the rebellion of 1799-1803, they eventually saw value in improving conditions - which is what the British were working for.

It would be a mistake, though, to think that the Caledon Code was a result of any particularly enlightened thinking.

It was, instead, a “very particular colonial project.”

One of the most significant voices that influenced the development of the Code was that of the landdrost of Graff-Reinet, Honoratus Mynier, who had attempted to broker peace during the rebellion of 1799-1803, and who had voiced his concerns both over uncontrolled violence between masters and servants, and over an alliance between the KhoeKhoe and the Xhosa.

“As a result, he entertained complaints made against trekboers by Khoi servants. In the parlance of the trekboers, Maynier had opened his doors to the 'heathen' - a policy that earned him the reputation of being the 'attorney' and 'nephew' of Khoisan servants.” (Dooling 2005)

He was thus removed from office following the change in administration in 1795, but was returned to his post in 1799, and given the task of restoring order to the frontier.

Mynier had already suggested (also during the rebellion) the regulation of relations between masters and servants, which included the issue of labour contracts, the restriction of violence and cruelty towards servants, and the idea that “'Hottentot Captains' who had become 'particularly obnoxious' be granted land for occupation.” (Dooling 2005)

These ideas pleased General Francis Dundas, the acting governor of the Cape Colony, who believed that, “A system of contracts and registration was more likely to transform the 'Hottentots' into 'most useful and Industrious Servants', and if frontier settlers could be prevented from beating their 'servants "ad libitum"', the latter would be loath to desert the employers 'at every opportunity.' The most important lesson learned from the rebellion of 1799-1803 was that the Khoikhoi were not to be allowed to 'become wandering Tribes again.'”

According to Dooling, “The Caledon Code was not the imposition of enlightened metropolitan thinking, nor was it the making of reactionary trekboers in search of 'serf' labour. It was a very particular colonial project. It grew out of the particular form of colonial rule that was bred in the Cape Colony at the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth centuries. This was rule through local collaborators - on the one hand the reluctance and inability of British imperialism to fully stamp its authority on this colonial outpost, and, on the other hand, the adaptability of local elites to a new form of imperialism. And last, but not least, the 'Hottentot Code' was the outcome of the long eighteenth-century struggle between masters and servants in the countryside, a struggle that culminated in the rebellion of 1799-1803.”

Racial and labour legislation in the Cape Colony following emancipation

Despite the eventual emancipation of the slaves, the influence of the Caledon Code is clearly seen in much of the ‘master-servant’ legislation enacted in the Cape Colony during the rest of the 19th Century - and right up to (and beyond) the Act of Union in 1910. This included the following acts, proclamations, and ordinances: (Quotes in this section from the O’Malley Archives; see also Glücksmann 2010)

- Ordinance No. 50 of 1828 - “freed the Coloured from the pass system and the risk of being flogged for offences against the labour laws," although “passes for other Africans remained on the books." The Ordinance also made clear the KhoeKhoe’s right to own land, “that they were no longer to be 'subject to any compulsory service to which other of His Majesty's Subjects ... are not liable',” that their children “could not be apprenticed without parental consent,” and that, “contracts of hire for more than a month had to be in writing and in no case should exceed a year."

- Master & Servants Ordinance No. 1 of 1841 - included workers of all races, defined the word ‘servant’ to include “any person 'employed for hire, wages, or other remuneration to perform any handicraft or bodily labour in agriculture or manufactures, or in domestic services'," and "imposed a penalty of twenty shillings for each month that a child, whether destitute or not, was illegally detained by an employer."

- The Masters and Servants Act No. 15 of 1856 - superseded the Masters and Servants Ordinance of 1841. "”Whereas the 1841 ORDINANCE had imposed a penalty of twenty shillings for each month that a child, whether destitute or not, was illegally detained by an employer, the ACT of 1856 decreed no penalty at all for the detention of children whose parents or guardians were still living, and altered the penalty for the detention of destitute children to 'not more than twenty shillings nor less than five shillings'." This was "designed to enforce discipline on ex-slaves, peasants, pastoralists, and a rural proletariat," because while it was “nominally colour-blind, the penalties are invoked only against the darker workers." Offences under the Act fell into three categories: "breach of contract, indiscipline (such as disobedience, drunkenness, brawling and the use of abusive language) and injury to property. Besides fines (as mentioned above), penalties also included imprisonments of various time lengths.” O’Malley notes that, “this act was not repealed until 1974 (see Riley 1991: 138), while it was amended at least twice (1873 and 1926).”

- The Kaffir (sic) Pass Act No. 23 of 1857 - banned the Xhosa from entering the Cape Colony except to work.

- The Kaffir (sic) Employment Act No. 27 of 1857 - "stipulated that Xhosa had fourteen days to find employment after the expiration of a contract." O’Malley notes that both Acts 23 and 27 of 1857 were “amended in 1867 (possibly by the VAGRANCY ACT),” which itself was amended by the ...

- Masters and Servants Amendment Act of 1873 - which “discriminated against servants employed on farms by exposing only them to sentences of imprisonment with hard labour, spare diet and solitary confinement ... magistrates were given the power to impose fines, and not imprisonment alone, on all other servants; while employers were for the first time made liable to imprisonment for breaches of contract."

- The Peace Preservation Act No. 13 of 1878 - which required all Africans to hand in their rifles.

- The Vagrancy Amendment Act No. 23 of 1879 - which "gave property owners or their representatives the right to apprehend 'idle or disorderly' persons 'wandering over any farm or loitering near a dwelling place, shop, store, kraal or any other enclosed place or loitering upon any road crossing a farm' "(Allen 1992: 191).” This Act, "supplemented the pass laws by prescribing a maximum of six months' imprisonment with hard labour, spare diet and solitary confinement for any 'idle and disorderly person' " (Simons & Simons 1969: 39). Since "the onus of proof was placed on the Africans who were arrested it was obviously in their interest to carry passes when they travelled" (Allen 1992: 191).”

- The Native Labour Regulation Act No. 15 of 1911 - which "reserved farm workers for white agriculture, closing the Orange Free State and considerable tracts of Natal, the Transvaal and the Cape to mine recruiting." This Act, “also "reduced the industrial power of blacks by making strike action by them a criminal offence" (Davenport 1987: 531). Furthermore, it imposed the "first statutory obligation ... to compensate Africans for injuries. The benefits ranged from £1 to £20 for partial incapacity and from £30 to £50 for total permanent disablement."

- The Natives Land Act No. 27 of 1913 (also known as the Natives Land Act, or the Bantu Land Act) - which “set aside 7.3% of the total South African land area as reserves where to accommodate the 'Native' population (Lapping 1986: 73+87). It also put certain restrictions as to the possibility for 'Natives' to buy and/or own land outside the reserves (Christopher 1994: 32f). It "not only helped white landlords to remove black sharecroppers, but held out prospects for the easier recruitment of labour for the mines by proposing to enlarge the recruiting areas, the reserves" (Davenport 1987: 531).” This act also prohibited whites from buying or occupying land in the reserves. “It was stated in parliament, at the time, that the purpose of the Act was to ensure the territorial segregation of the races. This stated purpose has generally been accepted, by politicians as well as social scientists, as a sufficient explanation for the Act which has come to be regarded as the cornerstone of territorial segregation. Recently, however, some writers have argued that the Act can be interpreted as an attempt to remedy the shortage of African labour on White farms, and to prevent Africans utilizing communal or private capital from repurchasing European owned land which had been acquired by conquest" (Wolpe 1972: 71).”

Conclusion: slavery and labour in the Knysna Forests in the 19th Century

While we have been unable to provide much hard evidence for the conditions under which black, coloured, KhoeKhoe, and other non-Europeans were required to work in the Knysna Forests from the end of the first Dutch occupation of the Cape in 1795 to the end of the 19th Century, this article has outlined the history of slavery in the Cape Colony under both Dutch and the British, and shown how the institution of slavery influenced racially discriminatory regulation throughout the 19th Century - and well into the 20th - which allows readers to draw their own conclusions regarding local conditions.

- Please now read our next article in this series: ‘Labour conditions in the Knysna forests under apartheid.’

Slaves in George and Knysna

These comprehensive lists of slaves who were registered to three slave owners in the Southern Cape are offered as an indication of the number of slaves belonging to households in the region under British rule.

These lists were copied from slave registers now held in the Western Cape Archives in Cape Town.

In honour of the people whose names appear on these lists, the information about each person is presented in a different order than that in which it was entered in the registers, which list the date of registration and the sex of each slave in the first two columns, and provides their names only in column 3.

Key

- Name - Sex - Country of origin - Job description - Date of registration - Notes

- § = Slaves younger than 13 years on date of registration

Slaves owned by Johannes Ernst Terblans (George)

- Carolus - Male - 30 - Mozambique - Labourer - June 12, 1816

- Domingo - M - 30 - Mozambique - Labourer - June 12, 1816

- Juliana - Female - 35 ½ - This colony - Housemaid - February, 1817

- § Fortuin - M - 1 ½ (mother, Juliana) - This Colony - February, 1817

- Clara - F - 36 - This Colony - Housemaid - July, 1827

- Goliat - 55 ½ - Madagascar - Labourer - July, 1827

Slaves owned by Johannes Vosloo (George)

- Oranje - F - 50 - Madagascar - Registered August 8, 1816

- Pieter - M - 40 - Mozambique - Labourer - Registered August 8, 1816

- Safleur - M - 20 - Mozambique - Labourer - Registered August 8, 1816

- Roselyn - F - 40 - Mozambique - Housemaid - Registered August 8, 1816

- Goliat - M - 39 ½ - Mozambique - Labourer - Registered March 4, 1818 - Reported on (illegible) October 1829 to have died 18 July, 1829

- Sabina - F - 22 ½ - This Colony - Housemaid - Registered September 18, 1818 - Sold & transferred 15 February, 1825 to Anthony Christoffel Lombard of Grahamstown

- § Josia - M - 2 ¾ - This Colony - Registered September 18, 1818

- § Lea - F - Born 15 November, 1820, to Sabina - Registered February 12, 1821 - Sold & transferred 15 February, 1825 to Anthony Christoffel Lombard of Grahamstown

- Jolien - F - 25 - This Colony - Cook - Registered February 12, 1821

- Tamer - F - 30 - This Colony - Cook - Registered 5 April, 1823

- § Joab - M - born to Tamer, 10 August, 1822 - Registered 5 April, 1823

- Roset - F - 43 ¼ - This Colony - Housemaid - Registered 6 May, 1830

- § Dellina - F - Born to Tamer, 7 September, 1830 - Registered 18 October, 1830

Slaves owned by George Rex (Knysna)

- Damon - M - 26 - This Colony - Carpenter - Registered 8 October, 1816 - Sold & transferred 26 March, 1826 to William Walter Harding, George

- Primo - M - 40 - Batavia - Mason - Registered 8 October, 1816 - Sold & transferred 6 August, 1832 to JJ Rademeyer, George

- Columbo - M - 36 - Madagascar - Mason - Registered 8 October, 1816

- Ceasar - M - 45 - Malabar - Woodcutter Registered 8 October, 1816

- Anthony - M - 32 - Madagascar - Woodcutter - Registered 8 October, 1816

- Hector - M - 35 - Mozambique - Woodcutter - Registered 8 October, 1816 - Reported on the 27th (illegible) to have died on the 23rd April 1829

- Lousa - M - 30 - Angola - Gardener - Registered 8 October, 1816

- July - M - 30 - Mozambique - Shepherd - Registered 8 October, 1816

- Africa - M - 35 - Madagascar - Woodcutter - Registered 8 October, 1816

- Zamoree - M - 40 - Madagascar - Labourer - Registered 8 October, 1816 - Reported to have died 1 March 1822

- Catharina - F - 36 - Angola - Housemaid - Registered 8 October, 1816 - Transferred 6 August, 1832, to JJ Rademeyer, George

- Lilly - F - 32 - Mozambique - Housemaid - Registered 8 October, 1816

- Tereka - F - 13 - This Colony - Registered 8 October, 1816

- § Catherine - F - 11 - This Colony - Registered 8 October, 1816 - Transferred 11 August 1832 to J. van der Wat & Sons, George

- § Sylvia - F - 9 - This Colony - Registered 8 October, 1816

- § Cate - M - 9 - This Colony - Registered 8 October, 1816

- § Martha - F - 9 - This Colony - Registered 8 October, 1816

- § Cornelis - M - 7 - This Colony - Registered 8 October, 1816

- § Julia - F - 5 - This Colony - Registered 8 October, 1816 - Transferred on 9 August, 1832 to H.C. Ungerer, George

- § Abraham - M - 4 - This Colony - Registered 8 October, 1816

- § Isaac - M - 4 - This Colony - Registered 8 October, 1816

- § Selima - F - 2 - This Colony - Registered 8 October, 1816

- § Pamina - F - Born 18 February, 1817 to Catharina - This Colony - Registered 11 March 1817 - Transferred 6 August, 1839 to J.J. Rademeyer, George

- § Maria - F - About 6 - Angola - Housemaid - Registered 20 November, 1818

- § Sanet - F - 6 - This Colony - Registered 20 November, 1818 - Sold & transferred 16 December 1830 to G.J. Stroebel, George

- § Herman - M - 4 - This Colony - Registered 20 November, 1818 - Sold & transferred 16 December, 1830 to H.J. Ungerer, George

- § Saria - F - 3 - This Colony - Registered 20 November, 1818

- § 2nd Maria - F - 10 - This Colony - Registered 20 November, 1818

- § Carolus - M - Born 18 June, 1819 to Catharina - This Colony - Registered 26 July, 1819 - Transferred 6 August, 1832 to J.J. Rademeyer, George

- § Havier - M - Born 19 June, 1820 to Illegible) - This Colony - Registered 18 August, 1820

- § Paulina - F - Born 21 (illegible), 1822 to Catharina - This Colony - Registered 22 February, 1822 - Transferred 6 August, 1832 to J.J. Rademeyer, George

- § Charles - M - Born 22 March, 1822 to Tereke - This Colony - Registered 27 April, 1822

- § Fan - M - Born 5 January, 1823 to Maria 1st - This Colony - Registered 10 February, 1823

- § Harry - M - Born 9 April, 1824 to Catharina - This Colony - Registered 29 May, 1824 - Transferred 6 August, 1832 to J.J. Rademeyer, George

- § Frank - M - Born 22 June, 1824 to Jessica - This Colony - Registered 23 August, 1824

- § Letje - F - Born 4 December, 1824 to Sylvia - This Colony - Registered 26 January, 1825

- § Catharina - F - Born 16 November, 1825 to Maria 1st - This Colony - Registered 29 November, 1825

- § Fanny - F - Born 3 May, 1826 to Catharina - This Colony - Registered 1 June, 1826 - Transferred 6 August, 1832 to J.J. Rademeyer, George

- § Anje - F - Born 3 October, 1826 to Cafferine - This Colony - Registered 30 December, 1826 - Transferred to 11 August, 1832 to J. van der Wat & Sons, George

- § Rosina - F - Born 20 January, 1824 to Tereke - This Colony - Registered 10 March, 1824

- § Stoffel - M - Born 31 May, 1827 to Sannet - This Colony - Registered 10 August, 1827 - Sold & transferred 16 December, 1830 To G..J Stroebel, George

- § Tommy - M - Born 30 july, 1827 to Martha - This Colony - Registered 31 August, 1827

- § Hendrik - M - Born 22 November, 1828 to Cafferine - This Colony - Registered 16 March, 1829 - Reported on 26 January, 1830 to have died on 1 January, 1830

- § Kitty - F - Born 7 March, 1820 to Sereka - This Colony - Registered 13 April, 1829

- § Jenny - F - Born 20 September, 1829 to Martha - This Colony - Registered 10 December, 1829

- § Mietjie - F - Born 22 August, 1830 to Cafferine - This Colony - Registered 18 October, 1830 - Transferred on 11 August, 1832 to H.C. Ungerer, George

- § Charles - M - Born 24 November, 1830 to Sannet - This Colony - Registered 16 December, 1830 - Sold & transferred 16, December, 1830 to G.J. Stroebel, George

- § Bel - F - Born 26 July, 1831 to Sereka - This Colony - Registered 21 November, 1831 - Reported to have died on the 31st July last

- § Lenera - F - Born 6 February, 1833 to Sereka - This Colony - Registered 6 May, 1833

- § Primo - M - Born 12 May, 1833 to Martha - This Colony - Registered 21 September, 1833

- § Cato - F - Born 18 September, 1833 to Sabrina - This Colony - Registered 2 January, 1834

Author

This article in our series, ‘Knysna: Our timber heritage,’ was written for the Knysna Museum by Martin Hatchuel with the help of these fine people:

- Patric Tariq Mellet (author, researcher, Camissa Museum, Cape Town)

- Theo Stehle (forester, retd.)

- Members of staff of the Western Cape Archives, Roeland Street, Cape Town

Further reading

Pre-colonial people of the Knysna forests

Labour in the Knysna forests under apartheid

Select bibliography

- Dooling, W.: 'The Origins and Aftermath of the Cape Colony's 'Hottentot Code' of 1809’ - Kronos: Journal of Cape History, Volume 31, Issue 1, Nov 2005

- Dooling, W.: ‘Slavery, emancipation, and colonial rule in South Africa’ University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2007

- Foster, J, Secretary to the Law Department; Tennant, H, Barrister at Law; Jackson, E.M., Chief Clerk in the Master's Office (eds): Statutes of the Cape of Good Hope - Volume 1 - Volume 2 - Cape Town, 1867

- Fourie, J.: ‘Slaves as capital investment in the Dutch Cape Colony, 1652-1795’ - Stellenbosch Economic Working Papers: 21/11 December, 2011

- Fourie, J.: ‘The wealth of the Cape Colony: Measurements from probate inventories’ - Working Paper 268 in the journal Economic History Review, 2012

- Glücksmann, R.: ‘Apartheid Legislation in South Africa’ 2010

- Hatchuel, M.: ‘Now, If You’ll Look To Your Left… A Handbook for Tourist & Community Guides In Knysna and Plettenberg Bay’ - The Garden Route & Klein Karoo Regional Tourism Organisation, 1998

- Hengherr, E.: ‘Emancipation and after: a study of Cape slavery and the issues arising from it, 1830-1843’ - Thesis for M.A. degree, University of Cape Town, 1953

- Joubert, R.: ‘History of the Overberg and southern Cape Forests (1795 to 2011)’ - Knysna Museums, 2019

- Loos, J.: ‘Echoes of Slavery: Voices from our Past’ - New Africa Books, 2004

- Malan, A.: ‘Households of the Cape, 1750 to 1850: inventories and the archaeological record’ - University of Cape Town PhD thesis, 1993

- Martins, I.: ‘An Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade: The Effects of an Import Ban on Cape Colony Slaveholders’ - African Economic History Working Paper 43/2019, African Economic History Network, 2019

- Mellet, P.T.: ‘The Lie of 1652: A decolonised history of land’ - Tafelberg, 2020

- Mellet, P.T. & Camisssa Museum: ‘Ancestral-Cultural roots of origin - African & Asian enslaved’ - Unpublished (pers. comm.) 2020

- Mutton, J.F.: ‘Human rights in the Eighteenth-century travelogues of Francois Le Vaillant’ - Fundamina (Pretoria) vol.22 n.2, 2016

- Reekie, W.D.: ‘The Wood from the Trees: Ex Libri ad Historiam Pertinentes Cognoscere’ - South African Journal of Economic History, Volume 19, Issue: 1-2, September 2004

- Southey, N.: ‘Historia - From periphery to core: the treatment of Cape slavery in South African historiography’ - SciELO SA: The International Bibliography of Social Sciences (IBSS), Volume 37 Number 2, November, 1992

- Storrar, P.: ‘George Rex: Death of a legend’ - MacMillan South Africa, 1974

- Theal, GM.: ‘History of South Africa since September 1795’ - Swan Sonnenschein & Co., London, 1908

- Van Niekerk, J.: ‘George Rex of Knysna : a civil lawyer from England and first marshall of the Vice-Admiralty Court of the Cape of Good Hope, 1797-1802’ - Fundamina : A Journal of Legal History, Volume 16, Issue 1, January 2010

- Voss, A. E.: ‘‘‘The Slaves Must Be Heard:" Thomas Pringle and the Dialogue of South African Servitude’ - English in Africa, Vol. 17, No. 1, 1990

Share This Page