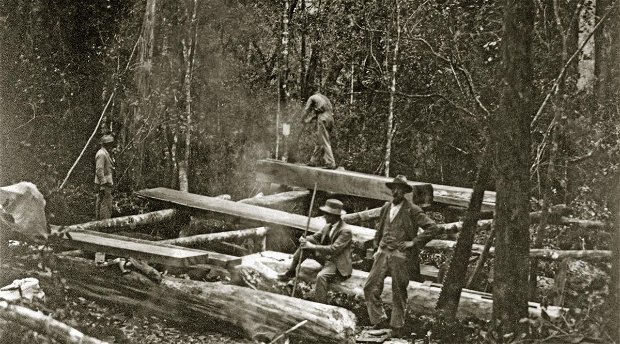

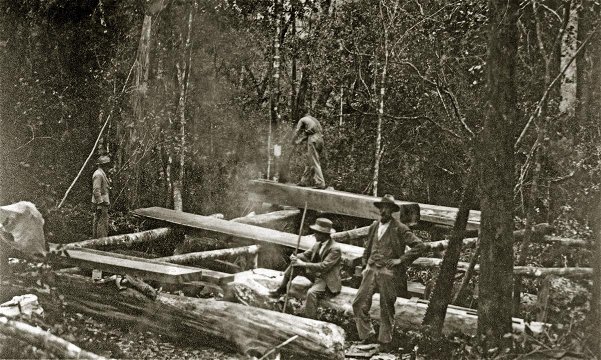

The woodcutters

The story of the people who harvested the timber from the early 1800s to the late 1930s

“They were as mysterious as the deepest forest gorge where few dare to venture, they could converse with one another in a secret code so that one of them could quickly drag away the bush buck - under the keepers noses - that lay strangled in an illegal snare. They admitted their deepest fears with the frankness of children, shared their last piece of bread or sweet potato with each other; took the axe from a weak one’s hands and hacked his wood for him.” Dalene Matthee, author of Kringe in ‘n Bos (Circles in a Forest), Fiela se Kind (Fiela’s Child), etc.

Although the government of the Cape Colony established its first woodcutter’s post in the Outeniqualand area (now the Garden Route) at Hoogekraal, near George, in 1777, industrial-level exploitation of the forests around Knysna probably only began when George Rex (1765 - 1839) bought and settled on the farm, Melkhoutkraal, in 1804.

Rex - who quickly established himself as a a timber exporter and trader - owned 33 slaves by 1805, and had license for 400 woodcutters by 1811. (Slavery was abolished throughout the British Empire - and therefore in the Cape Colony - on 1 December, 1834, although freed slaves remained ‘apprenticed’ to their former owners for a further four years. See ‘Slavery and Emancipation of Slaves’ on sahistory.org.za).

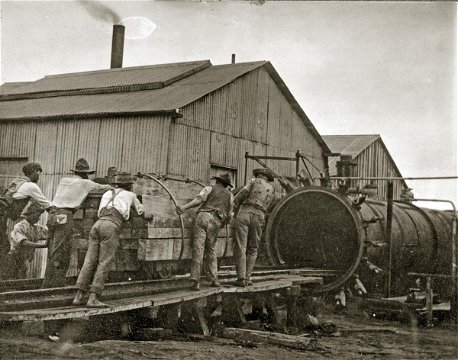

The economy of the Cape Colony, and, later, South Africa, needed Knysna’s timber (see The Knysna Forests), and it was the woodworkers who lived in the forests and felled the enormous trees by hand - and cut the logs into manageable sizes by hand, too - who became the first link in the chain that satisfied this demand.

Free and independent though they were, they remained desperately poor, selling their timber - often for pitifully small amounts (and, often too, in exchange for ‘good-fors’ or tokens redeemable at the merchant-owned general dealers’ stores) to the timber merchants, who exported it to markets in South Africa and abroad.

The woodcutter’s life

“The Woodcutter’s day started with the sun. He would either walk the few miles of forest trail to the tree upon which he was working or wake up beside it to the smell of a smouldering ironwood fire and old ash and the clean scent of fresh wood-chips. Soon there would be the fragrance of coffee and tobacco smoke and then, with the first shafts of sunlight, the ringing of axes would begin again. A man and his sons might spend as long as a month working a giant yellowwood or stinkwood tree.” Hjalmar Thesen, Country Days (David Philip, Cape Town, 1974)

Their homes were sometimes no more than crude huts - often just temporary structures, built close to whichever tree they were working - food was scarce (their diet often consisted only of sweet potatoes), and hygiene was poor. But nevertheless, they were, “self-employed, willing and able to work, but often lacked the necessary capital, training and, most important, the opportunity to benefit from their labours.

“In trying to account for the poverty of the woodcutter population, it is of little explanatory value to adopt the notion that they were 'prisoners of their culture' which implies 'that once a people has acquired a pattern of behaviour more suited to the past, once they have been imbued with values and norms of a bygone age, they can simply not adapt themselves to a modern economy.' On the contrary, the impact of 'modern economy', and more specifically merchant capital in the area, had more to do with the poverty of the woodcutters than their presumed 'backwardness' and 'laziness'.” - A.M. Grundlingh “God Het Ons Arm Mense Die Houtjies Gegee: Towards a History of the 'Poor White' Woodcutters In the Southern Cape Forest area c. 1900-1939” (University of the Witwatersrand. Download .pdf (675 kb) here).

End of the woodcutters’ era

Both the timber merchants and the government began to understand that the natural forests couldn’t last forever, and some conservation measures were put in place in the late 1800s, and plantations of exotic pines, wattles, and gum trees were established in the early 1900s to supplement the supply the country’s timber supply.

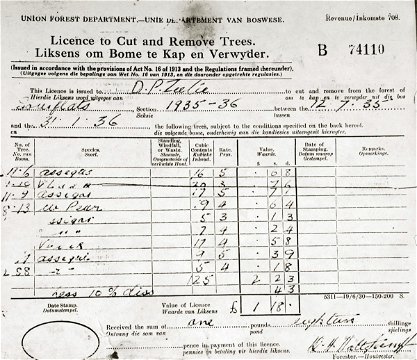

In 1914 the woodcutters were made to register for their rights to purchase trees for felling. Each woodcutter was required to produce a minimum of 25 cubic metres of timber per annum (for which they were paid about one pound per metre) - but even this was too much for the forests, which couldn’t replenish themselves at the rate at which they were being felled.

- Further reading: SANPark's Forest Legends Museum

Share This Page