Labour in the Knysna forests under apartheid

What was life like for workers in the Knysna Forests under Apartheid?

While there was little social divide at the beginning of the 20th Century between coloureds and ‘poor whites’ - both as woodcutters and as employers - interventions aimed at uplifting white people that began in the 1920s soon left coloured people far behind. For black people, though, work was only occasionally available - and this would only change in the 1990s.

In our earlier article, Slavery and labour in the Knysna forests in the 19th Century, we showed how the institution of slavery in the Cape Colony in the 18th and 19th Centuries influenced and informed racial legislation in the period up to and beyond emancipation on 1 January, 1834 - and how that continued into the 20th Century, when the British Parliament passed the South Africa Act of 1909, which combined the former colonies of the Cape of Good Hope, Natal, Orange River, and Transvaal, and established the Union of South Africa as a self-governing dominion of the British Empire on 31 May, 1910.

We’ll now examine the reasons why forestry in the Southern Cape - including plantation forestry and the harvesting of indigenous forests - provided work almost exclusively for whites for most of the 20th Century, leaving little for coloured people, and only scraps for blacks in the period leading up to the first democratic elections in 1994.

These reasons included:

- The state of the forests;

- The rapid increase in the population of the area in the 1920s;

- The master-servant nature of national legislation; and

- The ‘poor white problem.’

Background: Forests, plantations, and the demand for timber

The history of forest conservation, and of forestry policies and practices in South Africa, is tied to the fact that natural, closed-canopy forests cover only a very limited portion of the country’s landmass: between 0.25% and 0.59% of the land surface, depending on which authority you prefer. (Grundy 2001)

The question of adequate supplies of timber has always been intimately connected with economic growth in South Africa. (Grundlingh 1987)

During the first 250 years of the colonial era, the natural, indigenous forests of the Cape (initially those around the Peninsula, and later the forests of the Southern Cape) were exploited for timber for wagon making, housing, tools, and so on.

Although intermittent efforts to control this exploitation began early in the period - van Riebeeck issued various placaaten (edicts or decrees) aimed at protecting ‘garden, lands and trees’ almost from the time he arrived here (Grundy 2001) - it was only with the promulgation of the Cape Forest Act of 1888 that the Knysna and Tsitsikamma forests (the country’s largest closed-canopy forests) finally received formal protection as South Africa’s first forest reserves.

This was an important and timely step, since demand for timber had begun growing rapidly in response to the rapid expansion of the railways across the subcontinent, and would grow even further when the country’s large-scale mining industry began to emerge after the discovery of diamonds in the Cape in the late 1860s, and of the gold-bearing reef on the Witwatersrand in 1886. (For an overview of the history of gold mining in South Africa, see: ‘Gold mining: Knysna's Millwood gold fields' on this site.)

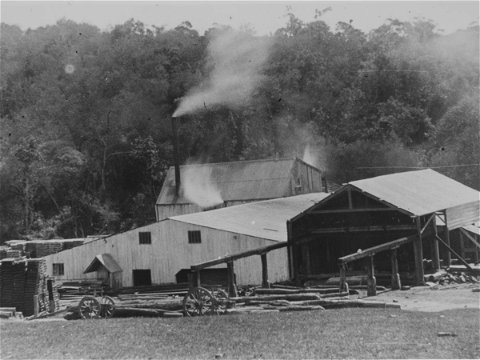

In the years before World War I, though, most of the commercial sawtimber (softwood) had to be imported, which made it excessively expensive - which, of course, was a major motivation behind the Union Forest Act of 1913, which replaced the Cape Forest Act.

Demand had grown quickly after the South African War (1899-1902), and increased exponentially at the onset of the World War in 1914: “timber imports ‘collapsed’ by 50 per cent or more from immediately before the war, and domestic prices of timber ‘rocketed’.” (Bennett & Kruger 2015)

In the period 1918-1922, timber and paper products made up more than half the value of goods imported into the country: “an annual average for the four years of just over £3 million.” (Bennett & Kruger 2015)

And by 1938, van Wyk would write that, “The timber consumption of the country has increased steadily owing to the general development of its mineral wealth and the resulting expansion and increase of industries and agriculture and the natural increase in the population. In 1921 the consumption of timber was 21,229,000 cub. ft., (601,100 cubic metres) and in 1934 this had risen to 43,409,000 cub. ft. (1,229,000 cu. m.), an increase of over 100 per cent, of which 21,857,000 cub. ft. (618,900 cu. m.) were imported, or nearly 50 per cent.”

Such constraints on costs and supply thus forced the national focus to shift from harvesting indigenous timber (which had previously happened mainly in the Southern Cape), to the development of a plantation industry - which in turn shifted the centre of timber production from the Southern Cape with its indigenous forests, to the eastern part of the country: the Natal Province (now KwaZulu-Natal) and the Eastern Transvaal (now Mpumalanga), where the state began investing heavily in planting pine, black wattle and eucalyptus (Reekie 2004).

This didn’t mean the state didn’t continue to plant in the Southern Cape, though. It certainly did - but not solely for economic reasons, as we shall now see.

Forestry in South Africa in the 20th Century: mainly for whites

The South Africa Act of 1909 (Act of Union) entrenched the master-servant relationship by, amongst others, denying the franchise to the majority of Black South Africans, while retaining qualified voting rights in the Cape Province for Black and Coloured males - rights that would later be withdrawn completely by the Apartheid government. (For a discussion of how this was achieved, please see Wikipedia: Coloured Vote Constitutional Crisis.)

The Act set the scene for a long period of legislative action that saw the economy develop from farming to mining to manufacturing, and eventually to services - but it did so supported by “a set of unusually coercive and discriminatory policies and institutions. The former protected the incomes of mostly white workers, through labour-market institutions and the welfare state, whilst the latter helped to depress the wages paid to unskilled, African workers.” (Nattrass 2010)

Politicians, the Dutch Reformed Church, and others had been worrying about South Africa’s so-called ‘poor white problem’ since long before the Act of Union.

The problem had largely been caused by the widespread failure of the subsistence pastoral (farming) economy that had supported large numbers of (mainly Dutch) settlers in the period up to the discovery of mineral resources - diamonds in the Kimberley area, and gold on the Witwatersrand - which triggered the industrialisation and modernisation of the national economy. (Cowlin 2018)

Additionally, the ‘Scorched Earth Policy’ instituted by Lord Kitchener, the commander of the British Forces during the South African War (1899-1902), contributed significantly to the impoverishment of the Afrikaners of the previously prosperous Transvaal and Free State Republics.

The expansion of the economy after the War led to an expansion in the (largely state-owned) timber industry, and by 1914 the Secretary for Finance was suggesting that the expanded Forest Service could provide employment opportunities for people who were out of work.

“In the Cape, some early plantations [closer to Cape Town] were established by using the labour of probationary prisoners and the inmates of rehabilitation centres, but mostly foresters relied on a mix of white, coloured, and African workers to do the unskilled work required.” (Bennett & Kruger 2015)

In the Southern Cape, though, unskilled work in the plantations was performed by poor whites. (Stehle, T., personal communication)

The work entailed preparing the land by hand or behind ox-drawn ploughs, tending to nursery stock, planting, weeding, and thinning - and it was both very arduous and poorly paid.

“The opportunity to hire cheap labour aided public, and most especially private tree-planting efforts for most of the twentieth century. Compared to other equivalent colonies, such as Australia, South African foresters probably benefitted from having to pay less for labour. South Africa’s leading expert on wattle, Ian J. Craib, noted in 1935, ‘South African plantations of wattle were only profitable because of cheap labour, indeed, these plantations would not exist without it’.” (Bennett & Kruger 2015)

The first forest schemes for white labour were established in 1916, when poor white woodcutters from Knysna were resettled at Jonkersberg (northwest of George) and in Franschhoek.

By 1922, when the Forestry Department committed to planting 10,000 acres a year, the poor white problem had become “an important political platform for Afrikaner politicians,” (Bennett & Kruger 2015) and it would remain so throughout the 1920s and 1930s.

The program that the government pursued reflected “concerns about racial mixing and the abject poverty of many of the poorest Afrikaners,” and was supported by the Afrikaner nationalists’ belief that “racial mixing, especially in Knysna, undermined white rule” (Bennett & Kruger 2015) - a belief that was reflected amongst many of the white woodcutters themselves, who “were known to be very proud of their white skins,” which they saw as giving them “superior standing.” (Stehle, T., personal communication)

And while the politicians were using resettlement and labour schemes as a way to alleviate white poverty, “and to demarcate racial boundaries which they believed had become blurred by impoverished economic conditions,” leading foresters “began to see settlement programs as helping to solve the Knysna woodcutter problem,” (Bennett & Kruger 2015) which had developed out of a need to protect the dwindling resource.

Following the Rand Rebellion - a series of miners strikes on the Witwatersrand in which more than 200 people died, and which caused the loss of more than 15,000 jobs - the government of General J.C. Smuts “created a white and coloured (but not African) labour bargaining system and developed a policy of preferential white labour employment in the rural sector. The rural program would employ whites, who included woodcutters but also many from recent migrants to the cities, and returned soldiers.” (Bennett & Kruger 2015)

This programme was strengthened when the Nationalist-Labour Pact, with General J.B.M. Hertzog as prime minister, took over from Smuts and his South African Party in the 1924 elections.

“The Hertzog government pursued the white agrarian program with greater intent, with the initial program aimed at including forest stations as training grounds to move poor whites onto permanent agricultural settlements.” (Bennett & Kruger 2015)

The forest settlement programme expanded rapidly from 1925 and into the 1930s in parallel with the rate of planting, which averaged between 12,000 and 14,000 acres per year (4,856 and 5,665 ha), with a peak of 15,642 acres (6,330 ha) in 1927.

But none of this benefitted black or coloured workers - which was a direct result of a policy decision that was taken in 1916.

In 'Forest Policy in South Africa' (in the Empire Forestry Journal, July 1938), van Wyk noted that the Forest Department “requires a relatively large labour force apart from its technical and administrative staff. It is the policy of the government to use for manual labour, as far as possible, unemployed or indigent white people in preference to natives. These people are housed in settlements specially made for them. This policy was initiated in 1916. It was considered as one of the best means of relieving the acute distress then prevailing among the white people in some districts of the Union. Employment of a spasmodic character has been found from time to time to assist these people, but frequently it did not result in a permanent benefit either to them or the State. It was felt that the aim should be to provide work of a permanent nature and which would result at the same in the creation of a tangible asset to the country. By 1936 the number of settlements had reached nineteen, providing work for 1193 labourers; the total population living at them was 6072.”

Labour and the Carnegie Commission Report of 1932

In his 1919 report, the Acting Conservator, C.S. Ross, wrote that, "’Forestry Settlements for the Poor Whites, are still being maintained... with a partial measure of success but only in so far as an improvement in the welfare of the settlers is concerned’." (Reekie 2004)

This didn’t mean that those people were quickly absorbed into the country’s modernised economy, though.

In 1921, Dr. E. G. Malherbe (who would later serve on the Carnegie Commission - see below) had written in the Cape Times that, “Today we have over 100,000 so-called poor whites. They are becoming a menace to the self-preservation and prestige of our white people, living as we do in the midst of the native population which outnumbers us 5 to 1.” (Malherbe in Cowlin 2018)

Such concerns led to the establishment of the Carnegie Commission, which drew its name from its major funder: the Carnegie Corporation of New York - whose “involvement in South Africa has to be seen as part of a much larger project of expanding America’s influence and philanthropy in the English-speaking world.” (Cowlin 2018)

The Commission's findings were published in five volumes in 1932, and had two major effects: while their “manipulation of race theories [were] initially used to provide a justification for segregation between white and black” - which led to the incorporation of poor whites into the white middle class through a “combination of preferential employment policies, stricter segregation and inclusion in the Afrikaner Nationalist project” (Cowlin 2018) - they also served to ignite a powerful backlash against the welfare state which South Africa had been building up to that time: “In 1938-39, almost £10 million - or about 20 percent of total public expenditure - was budgeted by the Union government for what the new Department of Social Welfare called ‘services of an essentially social welfare nature.” (Seekings 2006)

Ironically, the Secretary for Agriculture and Forestry, P.R. Viljoen, worried that the woodcutters of the Knysna Forests had become “very privileged citizens” by 1938, since they enjoyed medical services, housing, transport to and from work, and remuneration “at a rate higher than that ‘of any other class of person employed on works of a comparable nature’.” (Viljoen in the 1938 Division of Forestry Annual Report, quoted in Reekie 2010)

Viljoen also worried that the woodcutters had become too soft: “So attractive was the benefit package, that [he wondered] whether the workers would be ‘fit to be taken up eventually as independent members of the community’... Worse still, while the practice had always been uneconomic as far as forestry alone was concerned, recruits (despite the alleged efforts of the central Department of Labour to prevent it) tended to be less than in the best physical shape. In a job where stamina and strength were prerequisites this raised further the costliness of the scheme.”

Nevertheless, the Division of Forestry’s 1938 report notes that many of the woodcutters were leaving to seek better employment opportunities on irrigation and land settlements elsewhere in the country - a situation that caused a labour shortage “that in some cases necessitated the employment of temporary Native and other labour to attend to essential operations."

While this “reserve army of the Native unemployed would only ever be mobilised on a temporary basis, and then only to fill gaps while the privileged checked out their prospects in other fields where the grass might be greener” (Reekie 2010), its deployment did come at a time when the Department ended the recruitment of poor whites as labourers, when opportunities for employment for white men were growing rapidly in other sectors throughout the country, and when recruitment for military service in the Second World War was reaching its peak.

And the War, of course, was followed by the election of the Nationalist Party in 1948.

Population of the Southern Cape in the early 1900s

The labour situation in the Southern Cape in the early 1900s was also affected by the demographics of the area - although those demographics had been dictated by government policy at least since Ordinance No. 50 of 1828, which repealed the Caledon Code of 1809.

“Basically, it freed the Coloureds from the pass system and the risk of being flogged for offences against the labour laws. However, while passes for Khoikhoi were abolished, passes for other Africans remained on the books... Thus, passes were abolished for the Khoisan, their right to land ownership was at last made clear, and they were no longer to be subject to any compulsory service to which other of His Majesty's Subjects were not liable.” (Glücksmann 2010) (See 'Slavery and labour in the Knysna forests in the 19th Century' on this site.)

Moving into the 20th Century, Black people aren’t even mentioned in the Magistrate’s Report for the District of Knysna for 1920 - although we read that, “Of white and coloured labour skilled and otherwise there is ample in the town for all local (i.e.) existing requirements. Farm labour especially during harvesting has been somewhat scarce. The demand being always in excess of supply.” (Cape Archives 1KNY8/5)

In 1928, though, the Magistrate’s Report listed the “European” population of the “810 square mile” (2,098 sq km) District of Knysna as 6,404 (unchanged from 1927); the “Native” population as 550 (down from 600 in 1927); the “Coloured” population as 5,800 (unchanged from 1927); and the “Asiatic” population as 5 (up from 3 in 1927). (Cape Archives 1KNY8/5)

The white population of the George, Knysna, and Humansdorp districts was growing rapidly, though, rising from 18,623 in 1911 to 23,179 in 1921. (Grundlingh 1987)

This was happening as a result of:

- The economic crisis in the Prince Albert-Willowmore-Oudtshoorn region that resulted from the collapse of the international ostrich feather market in 1913-14, which forced farmers and bywoners (landless tenant farmers) to migrate - mostly to the Southern Cape;

- A severe drought throughout the Karoo in 1916, during which many bywoners were evicted from their homes; and

- Government programmes to address the ‘poor white problem’ (see below).

This population increase coincided with a favourable market for timber during and after the First World War, which meant that work was relatively easy to find in the Southern Cape - although, of course, the upliftment of white woodcutters contributed significantly to the failing fortunes of black and coloured labourers in the local timber industry.

The woodcutters: white and coloured

Skilled management work in the Knysna Forests had been the exclusive preserve of white men for some time. A recruitment advert in the Cape Times of 12 March, 1892, for example, stated that, “Applications are invited for vacancies in the staff Foresters in the Knysna Conservancy… Young married men of European extraction are preferred, used to a country life, and able to read and write in English, and write in Dutch.” (Cape Archives AGR25)

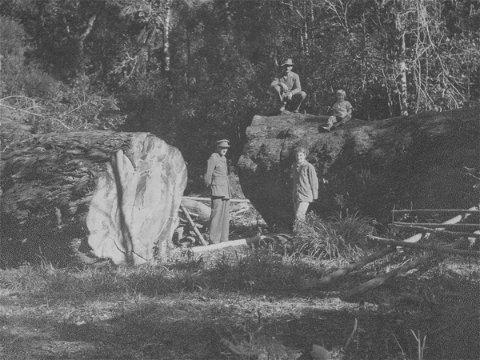

Most of the people who worked the timber itself were white, too: the men who felled the trees, cut them into logs by hand and sawed them into planks by hand, or slipped them out of the forests and transported them to the sawmills or the timber merchants in town - came generally from the white community.

But they belonged to ‘a different class.’

“In the early 20th century three 'classes' can be discerned amongst the whites in the forest belt: firstly the landowners, forest owners, merchants and professional men; secondly and below them, those in permanent employ as artisans, clerks and other functionaries; and thirdly at the bottom of the social pyramid ('at a judicious distance and knowing how to keep their place') the 'poor whites'. There was a considerable social distance between the underprivileged and the more well-to-do, the latter often treating the poor with contemptuous disdain. The wealthy and the destitute lived in two worlds as if they had nothing in common but… in an historical-materialist sense the social relationship between the two was intimately intertwined and ridden with conflict. There was, in fact, a direct correlation between the riches of the one and the poverty of the other.” (Grundlingh 1987)

The woodcutters weren’t all white, though: about 1,200 of them registered with the Conservator of Forests when it became compulsory to do so in 1913, and of these, 195 (17.5%) were coloured - but none were black. (Grundlingh 1987)

Significantly, government control “rigorously excluded” non-registered tree fellers, and “new entrants were not admitted.” (Reekie 2004)

This resulted in a small cohort of forest workers among whom, according to Grundling, the “difference in the material conditions” between poor whites and coloured people was small.

“Independent 'coloured' woodcutters worked under the same circumstances and regulations as whites in the forests and shared the same physical deprivations and mental outlook on their work and environment. Occasionally, whites might have employed 'coloureds’ to help them, but the reverse also happened. In the immediate aftermath of the Anglo-Boer War for instance, discharged 'coloured' muleteers from the British army moved into the Knysna area from missionstations at Bredasdorp, Mossel Bay and Bethelsdorp, and in an attempt to benefit from rising timber prices at the time, hired local 'poor white' woodcutters to assist them in collecting wood. Admittedly some white woodcutters might have resented the fact that their social standing was on a par with that of 'coloureds', but ultimately hard material realities blurred and obliterated attitudes of presumed superiority. One expression of this communality is to be found in a petition of I907 to the Cape government, calling for a greater allocation of trees, and signed by 118 woodcutters of whom 63 were coloured. Significantly the petition closed with an appeal for assistance, 'whether we are English, Dutch or Coloured’.

“'Coloureds' and 'poor whites' furthermore shared the same residential areas. At Suurvlakte in the George district, and at Ouplaas and Soutrivier, close to Knysna, as well as deeper in the forest area of the district at the Crags, Harkerville and Kraaibos both groups occupied their small-holdings on the same conditions, and according to an investigation in 19331 lived 'cheek by jowl' and regarded each other as 'complete equals'. Under these conditions marriages between whites and 'coloureds' were not at all uncommon. To some ‘poor white' women, marrying into a 'coloured' family might, at times, have meant a distinct improvement of their position. In 1933 It was reported 'that there are white girls who are only too glad to become the wives of coloured men, whon they have known since childhood and who were more prosperous than the girls’ own white parents.' (Grundlingh 1987)

The Woodcutters Annuity Act of 1939

The age of the Knysna woodcutter came to an end with the promulgation of the Woodcutters Forest Annuity Act of 1939.

“These poor white (and coloured) woodcutters had sole rights to timber extractions, and received consistent political support and public attention in their constant appeals against restrictive regulation.” (Bennett & Kruger 2015)

They’d worked the Knysna and Tsitsikamma forests since the Dutch East India Company (VOC) had established its outpost in the George area in 1777, but after the VOC ended its monopsony (the Company was the only entity allowed to buy produce such as timber), and subsequently lost control of the Cape to the British altogether, the woodcutters began to eke out a meagre living by selling their timber to local merchants.

Nevertheless, the damage they caused was significant enough that the foresters had begun “exercising progressively stricter control over their felling from 1874 onward.” (Bennett & Kruger, 2015)

Although the Cape Parliament’s Forest and Herbage Act of 1859 had been designed to prevent illegal felling, the passage of the Forest Act of 1888, “which had as its objective ‘the better protection of forests’,” (Bennett & Kruger, 2015) gave added impetus to the foresters’ efforts.

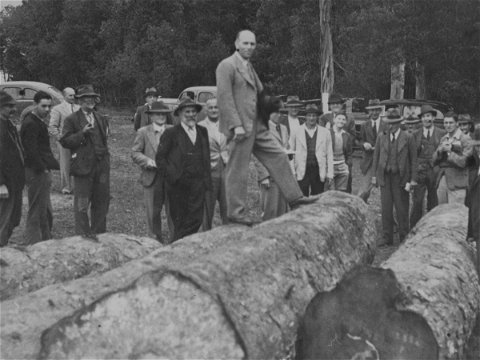

In his, 'Historical Review of the Development of Forestry in South Africa' the Director of Forestry, J.D.M Keet, estimated “a maximum of 2,000 woodcutters in the historical record.” (Bennett & Kruger, 2015).

This number had reduced to 1,500 by 1900, and to 1,269 by 1912, when formal registration was instituted (this system was ratified in the following year by the Forest Act of 1913).

“A registered woodcutter was officially supposed to derive his main source of income from working the timber allotted to him by the state, else his name could be deleted from the list and his license revoked. A woodcutters' board, consisting of the magistrate and a number of local luminaries, worked in coordination with the Forestry Department and closely monitored the situation. In addition, any woodcutter found guilty of contravening one of the numerous forestry regulations could be deprived of the right to work in the forests. Through the actions of the board (and also because the names of deceased woodcutters were struck from the list) the number of registered men was reduced to 557 by 1929.” (Grundlingh 1987)

This still didn’t have the desired effect, though. Since, “‘giving the sole right to the working of timber to the registered wood-cutters ... linked the question of forest management and the alleviation of distress’ ... it was often ‘necessary to sell very much more timber from the forests than what was considered permissible’.” (Bennett & Kruger 2015)

Eventually - for both conservation and social reasons - it was decided to annul the woodcutters’ rights to fell the trees altogether, and in compensation, Parliament passed the Woodcutters’ Annuities Act of 1939, which removed them from the forests altogether and provided the last of them (302 men) with modest lifetime pensions.

“The state-owned indigenous forests of the Southern Cape were granted a well-deserved rest.

“What was left... was a battlefield of devastation. It seemed best to leave the healing of the worst wounds to nature.

“In the early ‘sixties the natural recovery of the forest had progressed so far that it was deemed possible and desirable to take steps toward active rehabilitation. On the basis of intensive research and planning, a comprehensive system of natural forest conservation was developed and, in 1967, put into operation.” (von Breitenbach 1974)

- See ‘The woodcutters’ on this site.

Labour under Apartheid

The system of Apartheid placed strict and onerous controls on labour throughout the South African economy, which “even as late as 1970, was dependent on low-skilled labor in agriculture and mining. As a share of the economically active black population in 1970, about 40% of blacks were employed in agriculture, forestry and fishing (2.26 m people), while blacks employed in mining and quarrying comprised 11% (610 k people).” (Wilse-Samson 2013)

The nationalists, who came to power as a coalition between the Herenigde Nasionale Party (HNP) and the Afrikaner Party in the general elections of 1948, and who would merge to form the National Party in 1951, formalised segregation in every aspect of South African life via a large number of acts of law.

In 1971, Hepple wrote that South Africa had two labour codes - one for whites, one for blacks - and that, “in addition to the ‘Bantu’ laws, Africans are subject to various labour laws which impose additional handicaps upon them. They are not permitted to engage in collective bargaining through the industrial council system, like other workers. The government is firmly opposed to the unionisation of African workers and refuses to give legal status to their trade unions. Strikes are prohibited under heavy penalties. Disputes with their employers cannot be argued and resolved by African workers themselves but must be settled by government officials.”

Amongst the laws that would have had the most impact on workers in the forests of the Southern Cape, were:

- The Population Registration Act No. 30 of 1950, which “required people to be identified and registered from birth as one of four distinct racial groups: White, Bantu (Black African), Coloured and other. The act was one of the ‘pillars’ of apartheid. Race was reflected in the individual's Identity Number. A Race Classification Board took the final decision on what a person's race was in disputed cases;”

- The Group Areas Act No. 41 of 1950, which “forced physical separation between races by creating different residential areas for different races;”

- The Separate Representation of Voters Act No. 46 of 1951, which, together with the Separate Representation of Voters Amendment Act No. 30 of 1956, led to “the removal of coloureds and asians from the common voters' roll in the Cape and placed them on a communal roll. Africans in the Cape had already been removed from the common roll” under the Representation of Natives Act No. 12 of 1936;

The Prevention of Illegal Squatting Act No. 52 of 1951, which “gave the Minister of Native Affairs the power to remove blacks from public or privately owned land and to establishment resettlement camps to house these displaced people.” - The Bantu Authorities Act No. 68 of 1951, which “ provided for the establishment of black homelands and regional authorities and, with the aim of creating greater self-government in the homelands, abolished the Native Representative Council;”

- The Natives (Abolition of Passes and Coordination of Documents) Act No. 67 of 1952 (the pass laws), which “required all black persons over the age of 16 in all provinces to carry identification with them at all times. The pass included a photograph, carried details of place of origin, employment record, tax payments, and encounters with the police. It was a criminal offence to be unable to produce a pass when required to do so by any member of the police or by an administrative official. No black person could leave a rural area for an urban one without a permit from the local authorities. On arrival in an urban area a permit to seek work had to be obtained within 72 hours. The act repealed early laws, which differed from province to province, relating to the carrying of passes by black male workers (e.g. the Native Labour Regulation Act of 1911);”

- The Native Labour Settlement of Disputes Act No. 48 of 1953, which “introduced a formal system of racially segregated trade unions and effectively made strikes by Africans illegal in all circumstances;”

- The Reservation of Separate Amenities Act No. 49 of 1953, which “forced segregation in all public amenities, public buildings and public transport with the aim of eliminating contact between whites and other races;”

- The Industrial Conciliation Amendment Act No. 28 of 1956, which “provided that no further mixed unions would be allowed to register and sought to impose racially separate branches and all-white executive committees on existing mixed unions which refused to split. It prohibited all workers, black and white, from striking in essential industries and banned unions from political affiliations;”

- The Bantu (Prohibition of Interdicts) Act No. 64 of 1956, which “denied black people the option of appealing to the courts against forced removals. The act was repealed by the Abolition of Influx Control Act No. 68 of 1986.

- The Promotion of Bantu Self-Government Act No. 46 of 1959, which “allowed the transformation of reserves into ‘fully-fledged independent Bantustans’. It also resulted in the abolition of parliamentary representation for blacks. Blacks were classified into eight ethnic groups. Each group had a Commissioner-General who was entrusted with the development of a homeland for each, which would be allowed to govern itself independently without white intervention. The act was repealed by the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa Act No. 200 of 1993.”

- The Bantu Laws Amendment Act No. 42 of 1964, which "empowered the government to expel any African from any of the towns or the white farming areas at any time. It was the most rigid of the apartheid legislation so far. It provided the legal framework for stripping Blacks of most of their remaining rights in White areas in return for independence in their own tribal homelands;”

- The Bantu Labour Act No. 67 of 1964, which “prohibited Africans from seeking work in towns or employers from taking them on unless they were channelled through the state labour bureaux;”

- The Separate Representation of Voters Amendment Act No. 50 of 1968, which “formed the Coloured Persons Representative Council with forty elected members and twenty nominated members. It had legislative powers to make laws affecting Coloureds on finance, local government, education, community welfare and pensions, rural settlements and agriculture;”

- The Bantu Labour Relations Regulations Amendment Act No. 70 of 1973, which “gave Black workers a limited legal right to strike for the first time in 30 years;”

- The Industrial Conciliation Amendment Act No. 94 of 1979, which “set up an Industrial Court which was to busy itself with the interpretation of labour laws, and to hear cases of irregular employment practices such as contentious dismissals, wage disputes and the legality of strikes. Thus the act made it possible for blacks to participate in the legal machinery set up for collective bargaining. It also allowed Africans other than contract workers to form their own trade unions; thus it opened the way for the rapid growth of black trade unions in the course of the 1980s;”

- The Labour Relations Amendment Act No. 57 of 1981, which “abolished all racial distinctions with regard to union membership, and permitted the formation of mixed trade unions, but obliged even unregistered unions to open their premises, their accounts and their membership lists to the Registrar for inspection. Strict rules were also laid down to prevent any direct association or financial links between political parties and trade unions, whether registered or not, and to ban financial assistance to members of unregistered unions if they went out on strike;” and

- The Restoration of South African Citizenship Act No. 73 of 1986, which “returned South African citizenship to citizens of Transkei, Bophuthatswana, Venda and Ciskei (TBVC) who were born in South Africa prior to the granting of their homeland's independence or who had resided in South Africa permanently. It was not applicable to those TBVC citizens who were in South Africa temporarily seeking employment, studying or visiting, or indeed to those who had permanent homes in the TBVC areas. They legally remained aliens in South Africa. They were not actually subject to removal, but only due to a lack of official action. The restoration of citizenship rights was extended to around 1.750.000 people in total. Approximately eight or nine million were still technically aliens. The act was reformed by the Restoration and Extension of South Africa Citizenship Act No. 196 of 1993, which was repealed by sec. 26 of the South African Citizenship Act No. 88 of 1995.” (All summaries: Glücksmann 2010. See also:O’Malley Archives hosted by the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory.)

One effect of this enormous wall of legislation was that very few black people were allowed to live and work in the Garden Route.

According to Theo Stehle, a retired forest scientist and forest manager who began his career with the Department of Forestry as a student in the late 60s, “during my first encounter in ‘67 and ‘68 I met vast numbers of white labourers, and no non-white people were employed on the forest stations from Mossel Bay to the Tsitsikamma.

“Then when I returned to work here permanently in 1982, the demographics had changed, and most of the stations employed coloured labourers, with the whites having been transferred to bigger stations like Kruisfontein and Bergplass, and to the state sawmill in George.”

From his earliest years, he said, he remembers “only a small number of black people were allowed to work as contract labourers,” but they were “shunted back to the Transkei” when their contracts ended. (Contracts were valid for one year, and labourers were not allowed to bring their wives or families with them to the Southern Cape.)

Conclusion

The policies and institutions that implemented and enforced racial legislation in South Africa were set up first and foremost to protect the incomes of white workers, and as a result, “shaped the growth path of the economy such that high inequality continued over time.” (Nattrass 2010)

While this was as much the case for the Southern Cape as it was for the rest of the country, the situation in the George, Knysna, and Tsitsikamma districts was also heavily influenced by the presence of the country’s largest, natural, closed-canopy forests.

The timber market these forests attracted having produced generations of under-educated white woodcutters, this presented successive governments (Colonial, Union, Nationalist) with specific social challenges - although, as far as those governments were concerned, those social challenges really applied only to one, ‘lower class’ of white people.

Which - as far as the timber industry went - left the majority out in the cold.

Author

This article in our series, ‘Knysna: Our timber heritage,’ was written for the Knysna Museum by Martin Hatchuel with the help of these fine people:

- Philip Caveney (Knysna Historical Society)

- Theo Stehle (forester, retd.)

- Members of staff of the Western Cape Archives, Roeland Street, Cape Town

Further reading

Pre-colonial people of the Knysna forests

Slavery and labour in the Knysna forests in the 19th Century

Select bibliography

- Alexander, R. & Simons, H.J.: ’Job reservation and the trade unions’- Enterprise, Woodstock, Cape, 1959

- Bennett, B.M.: ‘The Rise and Demise of South Africa’s First School of Forestry’ - Environment and History 19 (2013): 63–85, The White Horse Press, 2013

- Bennet, B. & Kruger, F.: ‘Forestry and Water Conservation in South Africa (chapter: Afforestation: Politics, Labour, and Science, c. 1910–1935)’ - ANU Press, 2015

- Caveney, P.: ‘The Woodcutter Settlements of Knysna’ - Knysna Historical Society, 2017

- Cowlin, J.R. ‘Pathways to understanding poor white poverty in South Africa 1902 to 1948’ - Master of Arts thesis, Faculty of Humanities / History, University of Stellenbosch, 2018

- Glücksmann, R.: ‘Apartheid Legislation in South Africa’ - ra.smixx.de, Hamburg, 2010

- Government of the Union of SA.: ‘Forest policy in South Africa’ - A report submitted to the FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United States), 1951

- Grundlingh, A.: ‘God het ons arm mense die houtjies gegee': towards a history of the 'Poor White' woodcutters in the Southern Cape forest area c. 1900 - 1939’ - Paper presented at the Wits History Workshop: The Making of Class, 9-14 February, 1987

- Grundy, I & Wynberg, R.: ‘Integration of Biodiversity into National Forest Planning Programmes - The Case of South Africa’ - Paper prepared for an international workshop on 'Integration of Biodiversity in National Forestry Planning Programme,' Centre for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), 13-16 August 2001

- Hepple, A.: ‘Job reservation - cruel, harmful and unjust’ - The Black Sash, July, 1963

- Hepple, A.: ‘South Africa: Workers under Apartheid’ - An International Defence and Aid Fund pamphlet. Second Edition, 1969

- Mariotti, M.: ‘Labor Markets in South Africa During Apartheid’ - Australian National University, 2009

- Morrell, R. (ed): ‘White but Poor - Essays on the History of Poor Whites in Southern Africa 1880-1940’ - University of South Africa, 1992

- Nattrass, N. & Seekings, J.: ‘The Economy and Poverty in the Twentieth Century in South Africa’ - CSSR Working Paper No. 276, July 2010

- O'Malley, P.: O’Malley Archives hosted by the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory

- Reekie, W.D.: ‘The Wood from the Trees: Ex Libri ad Historiam Pertinentes Cognoscere’ - South African Journal of Economic History, Volume 19, Issue: 1-2, September 2004

- Roach, T.R.: ‘The White Labour Forest Settlement Programme 1917-1938’ - Master of Arts Dissertation, University of Witwatersrand, 1989

- Scher, D.M.: ‘"The court of errors" - a study of the High Court of Parliament crisis of 1952’ - Kronos : Journal of Cape History, Volume 13, Issue 1, Jan 1988

- Seekings, J.: ‘The Carnegie Commission and the Backlash Against Welfare State- Building in South Africa, 1931-1937’ - Centre for Social Science Research (CSSR) Working Paper No. 159, May 2006

- Stehle, T.: Personal interview, October, 2020

- van Wyk, J.H.: ‘Forest policy in South Africa’ - Commonwealth Forestry Association, Empire Forestry Journal, Vol. 17, No. 1, July 1938

- von Breitenbach, F.: ‘Southern Cape Forests & Trees’ - Government Printer, Pretoria, 1974

- Wilse-Samson, L.: ‘Structural Change and Democratization: Evidence from Rural Apartheid’ - Columbia University, November 2013

Share This Page