Belvidere and the Duthie family

The story of the village of Belvidere – and its famous, Norman-style church – is largely the story of Thomas Henry Duthie, a son-in-law of George Rex, the ‘founder’ of Knysna

The land on which Belvidere stands is part of the original farm, Buffelsvermaak, which was granted to Pieter ter Blans, and which stretched from the Goukamma River to the Knysna Lagoon, and from the ocean to Sandkraal (now Westford). However, since land tenure in the Cape was at that time a haphazard affair, the colonial government allowed farmer Hendrik Barnard permission to graze his cattle on a portion of Buffelsvermaak known as ‘the loan place Uitzigt’ in 1795 – and officially granted him the farm Uitzigt in 1818.

In 1830, however, after Barnard passed away, George Rex of Melkhoutkraal – a wealthy landowner, timber merchant, and businessman (he had a number of stores throughout the district), who had arrived in the area in 1804 – bought Uitzigt from the deceased estate, thus acquiring the land we now know as Belvidere, Lake Brenton, Brenton-on-Sea, and Buffalo Bay, and bringing his total landholdings to 12,323 hectares (almost all the land in the Knysna River basin).

It was Rex who renamed the farm Belvidere – literally, ‘beautiful vista.’

During one of Rex’s many visits to the Cape, he met Lieutenant Thomas Henry Duthie and, much impressed by the dashing young soldier (and, no doubt, aware that the eldest of of his seven daughters – Elizabeth, 26; Anne, 21; Caroline, 17 – were all in need of husbands), invited him to visit his family in Knysna.

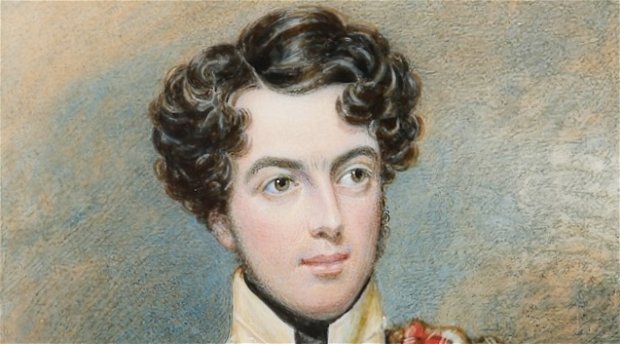

Thomas Henry Duthie

Thomas Henry Duthie was born in Stirling, Scotland, on 6 July, 1806. His father died when Thomas was about 12, leaving his mother to raise their four younger children on her own: the eldest, Archie, was already on his way to a career in the church when their father passed away.

Ms. Duthie entered Thomas in the military academy in Edinburgh when he was 19, and soon after, bought him a commission as an ensign in the 72nd Highlanders (the Duke of Albany’s Own Regiment), after which he was posted to Belfast, and later to Lilford in Donegal – and after two years in Ireland, to the Cape Colony, together with the rest of his regiment. Here, Thomas was put in charge of the construction of the Houw Hoek Road (now Sir Lowry’s Pass), although he was still only 23 years of age.

After completing the pass and being promoted Lieutenant in 1830, Duthie was granted two months leave to visit the Eastern Frontier, and during this time spent a week at Melkhoutkraal – where he fell in love both with Caroline, and with the farm Belvidere, which Rex had recently bought.

During Duthie’s second visit to the Rexes – in 1832, when Caroline was 19 – the couple became engaged. But Duthie was so enraptured of his new fiancée that he left leaving for Cape Town too late – and thus made his now legendary, record-breaking horseback dash back to headquarters in just five days: a ‘normal’ trip by cart would take three weeks, but Duthie left Knysna on the 6th of November, and arrived an hour before midnight – his cutoff time – on the 10th.

Thomas then applied for permission to leave the army, and the couple were married in Cape Town on 12 February 1833 – the first time Caroline had been “more than 20 miles away from home.” After a short honeymoon in the Cape, they boarded a ship for Britain, where their first child, Caroline, was born on the 21st of November, and where Thomas enrolled for courses in agriculture, botany, and natural history at the University of Edinburgh.

On their return to Cape Town, Thomas signed the Deed of Sale for the purchase of Belvidere on 7 October, 1834 – paying £750 for the farm (which Rex had bought for £679 17s 6d). Three weeks later, the Duthies returned to Knysna, staying with Rex for seven weeks, and then moving into tents at Belvidere while Thomas completed a cottage, which he built with materials organised earlier by Rex.

They moved into their permanent accommodation in 1835, and at first everything seemed idyllic, but within a year, Thomas was writing to Archie to ask whether he might return to Britain. He had, he said, problems with labour (slavery had been abolished in the Cape Colony on 1 January, 1834 – see Slavery and labour in the Knysna forests in the 19th Century) and, although he wanted to import English families to settle the land (and no doubt provide him with the social life he craved), his father-in-law was not in favour of the idea. The local farmers were “a regular set of sharks” and very uncivilised to boot, and he found farming and home life “hard toil and drudgery.”

In 1835, though, the Duthies received a visit from one of Thomas’s old school friends: a Captain James Alexander. Alexander had noticed “the large numbers of squatters” cutting timber from the forests of the district without licenses, and lamented this to the authorities. Possibly as a result of his recommendation, Thomas was appointed Supervisor of Crown Forests and Lands – Western Division of the George Districts, in December 1836, and quickly set about introducing extensive improvements to forest management in the region.

By 1838 – no doubt partly as a result of the income generated from his appointment – the Duthies were becoming “more settled and comfortable.” Also, Thomas was able to sell modest amounts of timber off the farm – and, to make matters simple, smaller coastal trading ships (up to about 150 tons) were able to navigate the lagoon as far inland as Belvidere, where loading and unloading took place. (Some of the timber was floated downstream – but it’s also worth remembering that in 1826, George Rex had built and launched his stinkwood brig, Knysna, at The Drift, some 6 km upstream from Belvidere.)

The Duthie’s second child, George Rex Duthie, was born on 4 April, 1836, and Archibald Hamilton Duthie on 1 October, 1839.

On the 3rd of April, 1839, George Rex died of a stroke. His sons, Edward and John, were appointed executors of his estate, and Thomas Duthie was made guardian of the five youngest Rex children.

Unfortunately, Rex’s homestead, Melkhoutkraal, fell to ruin quite quickly (possibly because he left it to his heirs severally, instead of to one child individually). Despite its decline, it was bought by Lt. Col. John Sutherland of the Bombay Light Infantry, who worried that “the five able-bodied sons watch this gradual display of all that is valuable around them with the utmost philosophy, instead of taking a blade or a plough and remedying the evil.”

According to Patricia Storrar (A Vista and a Vision: the Story of Belvidere, Knysna), “Sutherland, a liberal, who abhorred the slave system, put down at least part of the decay of the estate to the fact that too much reliance had previously been placed on slave labour. In fact, he saw the present decline of a once splendid estate as retribution for those who had exploited the unfortunate slaves in former times.”

From about 1840, and following Rex’s death, the Knysna district entered a period of relative productivity and creativity.

For the Duthies, more children were to follow: Thomas Henry Jr. on 6 July, 1840; Ann Buchannan on 5 February, 1842; Frederick Angus, 25 November, 1843; John James, 18 July, 1845; Maria Louisa, 14 May, 1848; Elizabeth Mary, 31 August, 1850; Margaret Haswell, 3 April, 1853; Jane, 27 June, 1855; and Amy Georgiana, on 12 March, 1857 (for a total of 12 …)

Thomas tried various farming activities during this time, often without success: salting fish for sale in Cape Town, angora goat breeding, and the breeding and salting of beef (this last in partnership with Frederick Rex – a partnership that lasted only three months). He eventually settled on cattle, and also bought Westford and Portland out of George Rex’s deceased estate to bring his total landholdings to 5,544 hectares.

To Duthie’s delight, the district began attracting more and more visitors from ‘civilised’ (read upper class, English-speaking) society – including the governor of the Cape Colony and his wife, Sir George and Lady Napier, and the Right Honourable Henry F.F.A. Barrington, whom Duthie had met by chance in George. Other welcome visitors included the Newdigate boys – William Henry (21) and George (19). William would decide to buy the farm Roodefontein in The Crags outside Plettenberg Bay, where he built Forest Hall, and from where he would marry Duthie’s daughter, Caroline. George returned to England.

Barrington came to stay with Duthie for a month in 1842, and bought the Portland farm from him for £400.

In 1848, Duthie began building a new house: his family was growing (and would grow considerably in the coming years), and they were receiving more and more visitors. The family hosted its first formal dinner in this new home in November, 1849.

The house followed a British (rather than Cape Dutch) design known as Colonial Georgian, with large doors and windows and an uncluttered facade. It was built of local materials – with much of the timber, including those for the house’s chief adornment, its grand staircase, coming from Barrington at Portland. Also, Duthie surrounded the building with decorative gardens – not necessarily common at the time – and planted a long avenue of oak and gum trees, some of which are still standing today.

In the late 1860s, by which time the fashion for importing roofing materials from the USA and the UK had begun, the house’s thatch roof was replaced with corrugated iron, while curved corrugated iron roofs and balustrades in the ‘Chinese Chipendale’ style were added to the balconies – all of which gave it the appearance by which we know it today.

Duthie’s desire for ‘civilised companionship’ was no doubt one of the drivers of his desire to establish a village at Belvidere, and so it was that he hired the services of the surveyor William Musgrove Hopley, who came to stay with the family in 1840.

Duthie and Bishop Gray having already decided on a site for a church, plans were drawn up for 157 residential stands with a commonage.

The first transfer of land took place on 15 April, 1850 (to Robert Squire, a descendant of John Squire, the first superintendent of government woods and forests in Plettenberg Bay), while Henry Barrington’s name appears a few days later as the purchaser of two of the plots.

Since any self-respecting village needs a post office, one of the front rooms of Belvidere House served this purpose at various times during its early history.

In 1857, William Roberts, Snr. bought the first of eight plots he was to acquire at Belvidere, and after his son, William, Jr., bought two adjacent stands in 1865, the pair consolidated their holdings to form erven 208 and 210, on which they built Ferry House – later to become known as the Brighton Hotel – and also a thatch-and-timber trading store, although this was demolished in the early 1900s. (Ferry House would again offer accommodation to travelers after restoration during the construction of Belvidere Estate in the 1980s.)

Belvidere Church

Thomas Duthie was always a religious man (his brother, Archie, was a clergyman) so, when Robert Gray was consecrated as the first Bishop of Cape Town in 1840, he made immediate plans to travel to the Cape to meet him. Within six weeks, Thomas and his son-in-law, William Newdigate, arrived at the Bishop’s official residence – then known as Protea, but now called Bishopscourt – seeking an audience to discuss plans for churches in the Knysna-Plettenberg Bay area. When they did finally manage to meet him, the Bishop showed them a series of plans drawn up by his wife, Sophie, who had made an extensive study of old churches in England for this very purpose.

Four months later, the Grays made the first of many visits to Belvidere, and, together with Duthie, settled on the old Norman-style design of the Belvidere Church – Holy Trinity Anglican Church Belvidere – as we know it today.

A building committee was formed including, amongst others, the Reverend William Andrews, Henry Barrington, and, of course, Thomas Duthie, and on the 27th of May, 1851, it published its first advertisement for labourers and artisans to work on the project.

The foundation stone was laid on 15 October, 1851, and the church was consecrated by Bishop Gray on the 5th of October, 1855.

Much of the skilled workmanship on the building was done by three Scottish masons brought out to the Cape by Bishop Gray – Alexander Bern and William and Colin Lawrence, who also built several other churches in the Colony. The ironwork was done by Thomas Noble and other employees of Francis Newdigate (Henry’s father), while William Page, also one of Newdigate’s employees, completed much of the woodwork.

The walls of the church were built of sandstone quarried locally, while many of the other materials were donated by Henry Barrington, who provided timber from his farm as well as slate and bricks imported from England. The latter were landed at Belvidere when the brig Apame delivered a load of his personal valuables and farming equipment.

The church’s bell was donated by Francis Newdigate, and was cast in London. When it arrived in Knysna, it was dropped in the lagoon during offloading, and remained under water for many months before it could be salvaged and finally installed in its rightful place. It pealed regularly until 1987, when it was discovered that its turret moved every time it was rung: its bracket had rusted away, and the stones of the turret had disintegrated. These were replaced (the stones were carefully removed, marked for position, and recreated by specialist masons in Mossel Bay) at a price greater than the £900 that the entire building had cost when it was originally built.

Thomas Henry Duthie died at the age of 51 on 13 August, 1857 – a little less than two years after the completion of the church. He left £150 per annum for his wife, and divided the rest of his estate between the eleven children alive at the time he made his will, eight months before his death: his daughter, Amy, hadn’t been born yet. His sons Archibald and John took up most of the responsibilities of farming at Belvidere: Archibald and his family moved into Belvidere House, and their mother moved into Ferry House, where she concentrated on raising her younger children.

In 1916, the chapelry of Belvidere was separated from the parish of Knysna to become the parish of Belvidere.

The mission school that was established in the parish – and the little coloured community that thrived there – would later be moved to the suburb of Hornlee under the Group Areas Act.

Brilliant botanist

Augusta Vera ‘Ave’ Duthie – daughter of Archibald Duthie and Augusta Vera Roberts and granddaughter of Thomas Henry Duthie – deserves special mention here, both for her many contributions to science, and for the effect she had on the history of Belvidere in the 20th Century.

Ave was born on 17 August, 1881 and received her early education at home under the governess Annie Armastrong, who joined the family when Ave was eight, and who would later teach most of the Belvidere children (of all races) – first in a back room of Belvidere House, then in a purpose-built wood-and-corrugated-iron building down by the lagoon, and finally in the Old School House that still stands close to the Belvidere Church.

Ave matriculated in 1898 and went on to study botany, physics, and mathematics, gaining her B.A. through the University of the Cape of Good Hope (later the University of South Africa) in 1901. In April 1902 she was appointed lecturer at Victoria College (later the University of Stellenbosch), where she founded the department of botany.

She studied privately for an M.A. at the University of the Cape of Good Hope, graduating in 1910, and she spent 1912 studying in Cambridge in England, and 1920 in Australia. In 1929, the University of South Africa awarded her a D.Sc. for her thesis ‘Vegetation and Flora of the Cape Flats.’

Ave served as head of the department of botany until 1921, developing it from scratch, and also developing its botanical museum and herbarium of the Stellenbosch district. After 1921, she confined her teaching largely to the morphology of the ferns, mosses, algae, and fungi.

She was an active researcher, “concentrating on the flora of the Stellenbosch flats. As a result of her painstaking efforts the flats became the most intensely studied botanical area in the country. The results of her studies were published in a number of papers in the Annale van die Universiteit van Stellenbosch between 1924 and 1940.” (S2A3 Biographical Database of Southern African Science)

She became a member of the Southern African Philosophical Society in 1906, retaining her membership when it became the Royal Society of South Africa in 1908, and being elected a Fellow of the Society in 1928.

Besides her numerous papers, Ave described thirteen new species of plants, and lent her name to one new species (Duthiastrum) and to genuses such as Restio duthieae, Romula duthieae, Psilacaula duthieae, Impatiens duthieae, and others. The botany department of the University of Stellenbosch named a small, 2.6 hectare portion of the Cape Flats where she did much of her fieldwork, the Duthie Reserve in her honour.

After the death of her brother, Will, in 1933, Ave took over responsibility for Belvidere, and, following her retirement in 1939, returned to live permanently in Belvidere House in 1940 – where she was shortly joined by her old governess, Annie Armstrong, who became a vital help to her. (After Annie died in July 1952, Ave commissioned a stained glass rose window for the Belvidere Church’s west wall, “To the glory of God and to the memory of Annie Armstrong.”)

Ave died on the 8th of August, 1963, leaving a carefully detailed will that directly influenced the development of Belvidere in the following years. It stipulated that all plots should be sold in pairs and, in order to prevent high-density development, forbade the subdivision of plots. It also gave the administrator of her estate, Andre Duminy, the power to sell plots to “approved purchasers who would, in his opinion, fit in with the traditional atmosphere of Belvidere” (Storrar, p. 120). She further stipulated that all new residences that were built must have a value of £1,500 or more. Additionally, the proceeds of any land sales were to be held in trust for the beautification and maintenance of the church and its grounds.

Since she did not leave Belvidere House to any one heir, a distant relative, surgeon Jock Marr, was appointed ‘nominative heir,’ and he and his wife moved in soon after Ave’s death. Although they redecorated the house and Ms. Marr tried to keep the farm going, they are reported to have found the challenges a little too great.

Jock died in 1968, and his son, John (also a doctor) took over as nominative heir, living in the house for the next six years.

From 1974, though, Belvidere House stood empty while various locals made plans for the redevelopment of the estate. In about 1977, they formed the Spring Lot Belvidere Co. (Pty) Ltd., and in 1983, a development plan was formalised - although it failed to draw investors.

In the mid 1980s, a local resident and designer, Gray Rutherford (who would also restore Ferry House), proposed a new vision for the estate which featured large parkland areas, and a formal harmony in the architectural design of residences and other buildings. This plan found favour with the Board of Executors development company, and, with the master plan coordinated by local town planner and landscape architect Chris Mulder, the ‘new’ development of Belvidere Estate was begun.

As part of the plan, the old Belvidere House was restored and opened as the Belvidere Manor country hotel – complete with a strategically placed gazebo with a beautiful vista (‘Belvidere’) of the Knysna Lagoon.

SOURCES

- Day, Pamela: ‘Thomas and Caroline A Knysna Diary 1830-1834,’ Pamela Day, Sedgefield, 2014

- Hatchuel, M.: ‘Now if you’ll look to your left… A Handbook for Tourist & Community Guides In Knysna and Plettenberg Bay’ The Garden Route & Klein Karoo Regional Tourism Organisation, George, 1998 (Revised 2001)

- Newdigate, Katharine: ‘Honey, Silk and Cider A Life Portrait of Henry Barrington,’ A.A. Balkema, Cape Town, 1956

- Nimmo, Arthur: ‘The Knysna Story,’ Juta & Company, Cape Town, 1976

- Parkes, Margaret & Williams, V.M.: ‘Knysna the Forgotten Port,’ Emu, Knysna, 1988

- Storrar, Patricia: ‘A Vista and a Vision The Story of Belvidere, Knysna,’ Rutherford Publications, Knysna, 1993

- S2A3 Biographical Database of Southern African Science: ‘Duthie, Miss Augusta Vera (botany)’

- Tapson, Winifred: ‘Timber and Tides The story of Knysna and Plettenberg Bay,’ General Litho, Johannesburg, 1967

Author

This article in the series 'Our Recent Past' was written for the Knysna Museum by Martin Hatchuel - July, 2022

Share This Page