Knysna’s fossil hominin footprints

Exciting discoveries! Forty fossilised hominin footprints in a beach-side cave near Knysna:

“The largest and best preserved archive of Late Pleistocene hominin tracks found to date.”

Were they made by humans like us?

If you’ve read our page, Middle Stone Age archaeology in Knysna, you’ll know that modern human behaviour emerged in our area - the Southern Cape (or the Garden Route, if you prefer) - during the Middle Stone Age.

Beginning around 162,000 years ago, anatomically modern humans like us began exhibiting the behaviours that define us. These include:

- systematically harvesting seafood (which indicates an ability to plan ahead);

- making complex tools by embedding tiny, precisely-cut stone blades into other materials such as wood or bone, and also using fire as a controlled engineering method of improving the quality of the stone (silcrete) they used for toolmaking; and

- making jewellery and using ochre (symbolling behaviour that indicates an appreciation of culture as well as the emergence of trade and commerce).

- Watch this video for a full picture of the archaeology that’s revealed the emergence of modern human behaviour; and

- Watch this video to see how toolmaking developed out of the humble South African braai!

To add to the wealth of archaeological evidence for this behaviour, there’s ichnological evidence, too: that is, fossil tracks that show that people and animals were moving through the landscape of the region tens of thousands of years ago.

In short - they left their spoor.

Hominin footprints

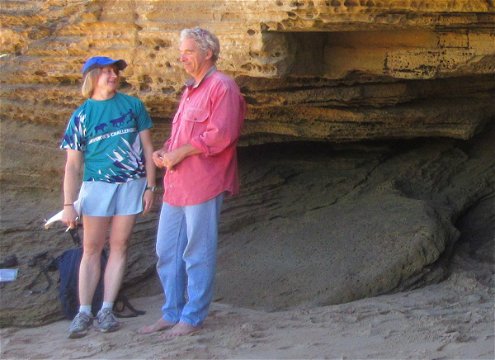

Knysna’s fossil hominin footprints were found in 2016 by a team led by Great Brak River-based researcher, Dr. Charles W. Helm,* a Research Associate of the African Centre for Coastal Palaeoscience at Nelson Mandela University, in a ten-metre-deep, beach-side cave situated within spitting distance of the Knysna Heads (the exact location is withheld to protect the integrity of the site).

Dr. Helm and his associates published A New Pleistocene Hominin Tracksite from the Cape South Coast, South Africa* in nature.com on 28 February, 2018 (see ‘Research’ below). (EDIT 1 November, 2020: The team described a number of 'new' sites after this article was published in April, 2020. Please see 'FOOTNOTE' below.)

As many as forty tracks preserved as casts are visible in the ceiling and side walls of the aeolianite rock (fossilised sand dune) of the cave. The researchers believe, though, that many more could be hidden in unexposed layers behind the cave (see ‘Geology’ below).

The tracks occur on two planes, with thirty five casts on one, and five on the other.

The shape and position of each track relative to its neighbours indicates that they were left by a number of individuals who were making their way down a sand dune some two kilometres inland from the seashore as it existed at that time.

Given the geology of the cave, Dr. Helm and his colleagues estimate that the tracks were made around 90,000 years ago - which makes this the only known hominin tracksite of its age on the planet.

“It adds to the relatively sparse global record of early hominin tracks, and represents the largest and best preserved archive of Late Pleistocene hominin tracks found to date. The tracks were probably made by Homo sapiens.”*

Significantly for the study of the palaeoclimate (ancient climate) of the region, both the cave itself and the area around it contain tracks made by species other than our own (see, ‘Yes, but how do we know they were hominins?’ and also ‘Crocodiles in the Garden Route?’ below).

Hominins

- Hominids are members of the family Hominidae: the great apes: orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees and humans.

- Hominines are members of the subfamily Homininae: gorillas, chimpanzees, and humans (but excluding orangutans).

- Hominins are members of the two genuses that constitute the tribe Hominini: chimpanzees (genus: Pan) and humans (genus: Homo).

How the site was found

Knysna’s hominin tracksite was found by Dr. Helm and his wife, Linda, and Knysna resident and fine artist, Guy Thesen, during a 9-year-long survey (2007 to 2016) of the aeolianites on the 350 km-long stretch of coast from Arniston to Robberg.

Although Dr. Helm found more than 250 tracksites in the Southern Cape during this period, this was the first hominin tracksite in the region: all the other sites contain only tracks of non-human species (see 'Crocodiles in the Garden Route?’ below).

South Africa, though, has two other known hominin tracksites, both of which are preserved in aeolianites, both created during the last interglacial period (Marine Isotope Stage 5e), and both containing just three tracks:

- Nahoon in the Eastern Cape - about 600 km to the east, laid down by our species (Homo sapiens sapiens), and dated to about 126 ka. This site was discovered in 1964, but collapsed soon after it was found. The tracks were recovered, though, and are now housed in the East London Museum.

- Langebaan in the Western Cape - about 400 km to the west, also laid down by our species, and dated to about 117 ka. This site was discovered in 1997, and its tracks were removed to the Iziko Museum in Cape Town.

These sites are currently considered the earliest known tracks made by our species. However, they were found before we learned of the existence of another homin from our immediate past - Homo naledi, who was only discovered in 2013, but who lived in Southern Africa until about 236 ka.

H. naledi may well have left tracks which have yet to be found. But, since they lived much earlier than H. sapiens, and also - as far as we know - inhabited an area more than 1,000 km north of Knysna (they were found in the Cradle of Humankind, 50 km from Johannesburg), we can assume that the Knysna trackways were indeed created by members of our own species. (See: Hominin tracks in southern Africa: A review and approach to identification by Charles W. Helm, Martin G. Lockley, Kevin Cole, TImothy D. Noakes & Richard T. McCrea).

Research methods

For their study of the Knysna hominin tracks, the researchers began by creating a standard field map of the exposed casts. They then determined the primary sedimentary structures of the rock, took samples for examination under microscopes, and compared the exposed rock facies to those of adjacent rocks (facies are “bodies of sediment that are recognizably distinct from adjacent sediments”). These facies were described through analysis of the structure of the sediment grain, and by examining the carbonate diagenetic signature of the rocks (that is, the combination of unique processes by which the individual rocks were formed, including “solution, cementation, lithification and alteration of the sediments during the interval between deposition and metamorphism.”).

The facies were also compared to other sites that have been accurately dated: one about 1 km along the coast, as well as others slightly further away.

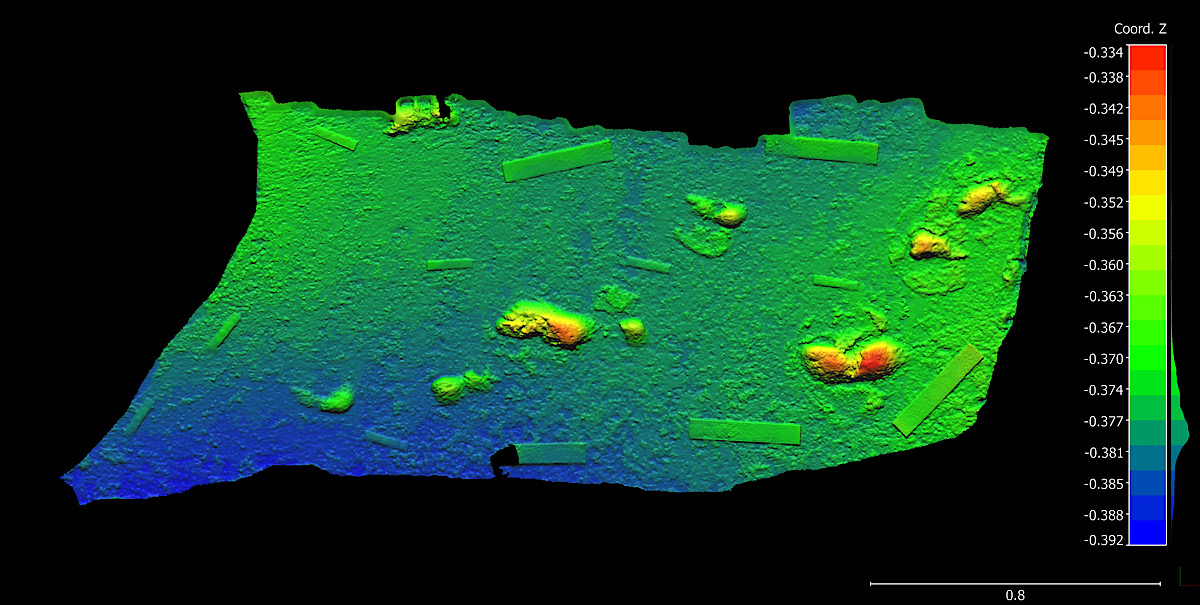

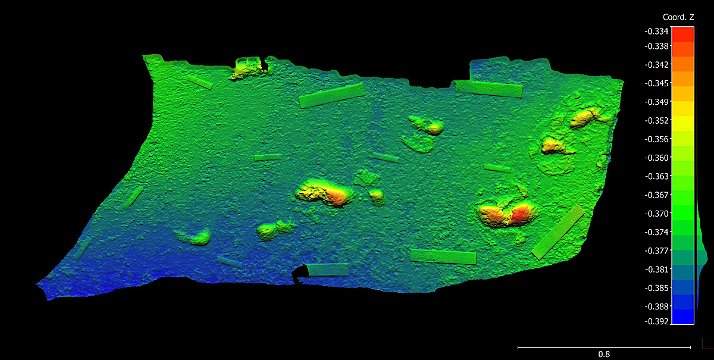

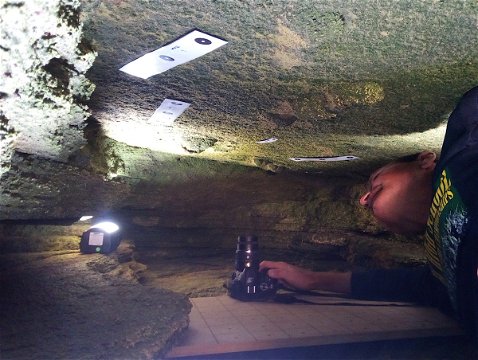

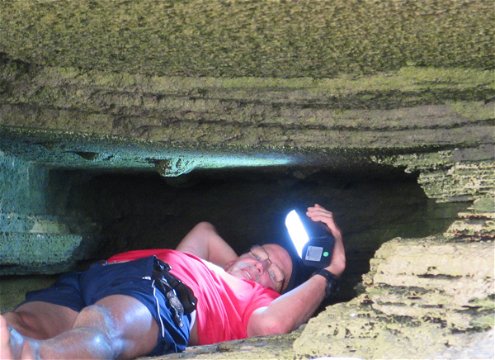

In order to create maps of the track surfaces, the researchers visited the site during 2016 and 2017 to record the positions, shapes, and sizes of the impressions via photography, GPS, and compass bearings. They also measured the sizes of the tracks, the distance between individual impressions, and so on. They took more than a thousand photographs in order to apply photogrammetry and obtain digital images from which they can create 3-dimensional replicas of the track surface. This is important because the cave ceiling (on which the tracks occur) and cave floor are often as little as half a metre apart, and the tracks are close to the observer’s nose and eyes, making it difficult to get an impression of the arrangement of the tracks across the entire surface.

The site was reported to Heritage Western Cape, and to the African Centre for Coastal Palaeoscience but, as mentioned above, “Site co-ordinates will not be publicly released until appropriate site protection measures have been undertaken, with the involvement of Heritage Western Cape.”*

- Photogrammetry: a portion of the ceiling of the cave in which Knysna's fossil hominin tracks were found. Vertical and horizontal scales in metres. Image: Charles. W Helm

Yes, but how do we know they were hominins?

Dr. Helm and his colleagues recognise that, “Rigour is required in the attribution of tracks to hominins.”* They therefore applied the criteria for identifying hominin tracks developed by Russel Tuttle,** a Professor of Anthropology, Evolutionary Biology, History of Science and Medicine at the University of Chicago, who analysed the 3.4-million-year-old footprints found by the palaeontologist Mary Leakey in Laetoli, Tanzania, and “determined that the creatures that left these prints walked bipedally in a fashion almost identical to human beings” (Wikipedia, Russel Tuttle).

Prof. Tuttle determined that in order to identify hominin tracks:

- The big toe must appear alongside four short, straight toes;

- The tip of the big toe must be rounded (“bulbous”), and not tapered;

- The tips of the big toe and the second and third toes must not be markedly longer than one another; and

- There must be evidence of a prominent arch in the middle and along the side of the footprint.

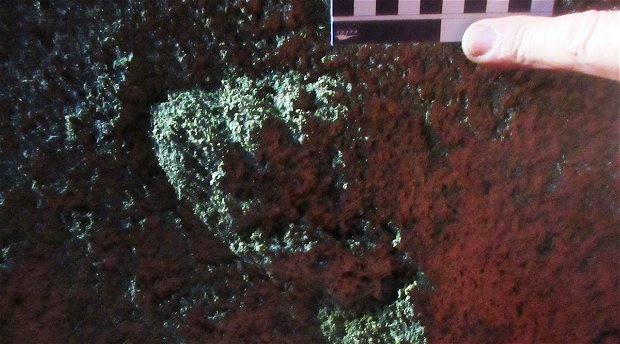

The casts found in the Knysna cave vary in their degree of preservation, with many showing signs of partial erosion. However, at least nine of the tracks found on the northern section of the site show clear imprints made by human toes as they sunk into relatively firm sand, while the tracks on the southern portion “appear to have been made in a softer substrate, which rarely preserves digital casts.”*

However, not all of the tracks on this site were made by hominins: two tracks made by even-toed ungulates (hoofed animals) “are visible on the southern surface of the main hominin track-bearing layer,”* while two more layers of tracks “occur 170 cm and 10 cm above the main hominin track-bearing layer,”* and “multiple tracks are also evident on the layer that forms most of the cave floor, 50–90 cm below the main track-bearing layer”* - all of which would most likely have been laid down quite close in time to the layer in which the hominin tracks were formed.

“A variety of non-hominin track types are represented, including tracks of elephant, various sizes of even-toed ungulate, large carnivore, giant Cape horse, probable juvenile ostrich, and small, unidentifiable tracks. Elsewhere along the beach and in the cliffs above there are further fossil vertebrate trackways, including a faint rhinoceros trackway, smaller equid tracks and buffalo trackways, as well as numerous invertebrate traces.”*

Geology

Aeolianites - or fossilised sand dunes (the type of rock in which local trackways are found) - occur intermittently along about a quarter of the Garden Route (South Cape) coast.

Knysna’s tracksite cave occurs in a steep cliff made up of aeolianite deposited against a bay-shaped formation of much harder quartzite formed during the Paleaozoic era.

Aeolianites are important elements of barrier systems on low-gradient, wave-dominated coasts. They’re considered sensitive indicators of the dynamics of ancient coastlines, providing information about fluctuations in sea levels, as well as the development, orientation, and geometry of sand dunes and other features of the geomorphology of these coastlines. They are also sensitive repositories of the palaeontology (the study of prehistoric species), archaeology (the study of human activity through the artefacts we leave behind), and ichnology (the study of tracks and traces) of the area.

“In the South African context they are key to understanding Middle and Later Stone Age archaeological sites and the associated palaeo-environments that our ancestors occupied.”* (Also see our page, Middle Stone Age archaeology in Knysna.)

Importantly for the Knysna hominin tracksite, the Southern Cape has not been subjected to major tectonic activity in the period since the local aeolianites were formed, which means that the site lies close to the angle at which it was laid down - that is, to the ‘angle of deposition’ at which they lay at the time the tracks were formed: between 10 and 30 degrees.

Geologically, the Southern Cape’s aeolianites belong to the Waenhuiskrans Formation of the Bredasdorp Group. The Waehnuiskrans Formation has been dated using various technologies such as Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL), Thermally-Transferred OSL, and amino-acid racemisation.

Most of the aeolianites in the Southern Cape were formed in the period between MIS 6 and MIS 5b (about 191,000 to 86,000 ka). Formations near the Knysna tracksite cave that have been dated by OSL include Castle Rock, which was formed 89 ka (with a variance of 6,000 years): Groenvlei, 91 ka (± 5 ka); Gericke’s Point, 92 ka (± 5 ka); and Buffalo Bay, 86 (± 5 ka, 91 ± 5 ka).

How the tracks were preserved

“In order for tracks to form, moist sand needs to be cohesive, which moulds the tracks. Rapid burial from further accumulation of dune sediment is then needed, then chemical changes occur which allow the dune surfaces to solidify. Finally shoreline erosion re-exposes the surfaces on which the tracks are registered. This can either be in the form of the original tracks, or of the sand layer that filled in the original tracks - these are known as natural casts, and that is what we see in the Knysna hominin tracks.” (Charles W. Helm, personal communication)

The cave mouth - which is situated on the beach at the level of high tide - is around 7 metres wide and 2 metres high. The cave itself stretches about 10 metres inwards, and the floor steps upwards from the mouth at an angle of around 25 degrees. At the back of the cave, the gap between the ceiling and the floor is approximately 50 cm.

According to Dr. Helm, “In its deeper portion it is rather tight, with just a small space between floor and ceiling. This might explain why the tracks were not discovered sooner - most people do not choose to crawl into narrow caves and look on the ceilings for tracks!

“The cave is exposed to the ocean forces, and is buffeted by high spring tides and storm surges. These forces have exposed the tracks for us to see, but are also actively eroding them. However, the hope is that over time these forces will also expose more hominin tracks.”

Crocodiles in the Garden Route?

Aside from Knysna’s hominin tracksite, researchers at the African Centre for Coastal Palaeoscience at Nelson Mandela University have identified more than 250 sites along the Southern Cape Coast that bear casts of vertebrates that lived in the region during the Pleistocene - a geological epoch during which significant climate changes raised the coastline as high as 13 metres above its present position (for example, during an interglacial period around 400,000 years ago) and drove it as far as 60 km south of its present position during a glacial period that occurred around 91,000 years ago.

Fossil evidence shows that the Palaeo-Agulhas Plain - the vast area of land that emerged from the sea south of the present-day Southern Cape during this last-mentioned glacial period - was populated by many species of mammals, including many that are now extinct.

For palaeoecologists, though, fossilised body parts provide only a partial picture of ancient ecosystems. Ichnology (the study of tracks and traces) is therefore important because it helps us further understand local palaeoenvironments: we know, for example, that giraffes and turtle hatchlings lived in the Southern Cape during the Late Pleistocene not because we’ve found fossilised bones from their bodies, but because we’ve found the fossilised tracks they left behind.

Information about the paleoenvironment is crucial to our understanding of the origins of modern human behaviour (see, Early humans thrived in this drowned South African landscape), and may also be important to our current understanding of human adaptations to climate change.

In a paper published in the South African Journal of Science on 26 March, 2020 - Pleistocene large reptile tracks and probable swim traces on South Africa’s Cape south coast *** - Dr. Helm and his colleagues discuss the discovery of fossil tracks left behind by two species of large reptile not previously known to have occured in the region (either then or in the modern era): the Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus), and the water monitor (Varanus niloticus).

In addition, the researchers also identified swim traces left behind by these large reptiles which were probably created in a lagoon setting. (These are the first crocodilian swim traces to have been found in Africa, although a similar example of a hippopotamus’ swim traces has been reported from Kenya).

Another exciting discovery in the Southern Cape: two Middle Stone Age artefacts were found embedded in the same palaeosurface as crocodile, mammal, and avian trackways.

According to Dr Helm in his article, Fossil track sites tell the story of ancient crocodiles in southern Africa, “We cannot be certain what they were used for, as we were not permitted to remove them for detailed analysis. But their presence suggests something which had not previously been documented: a spatial and temporal association in this environment between humans and large reptiles, or at least mutual use of habitat.”

Summary: the significance of Knysna’s hominin tracksite

- Knysna’s hominin tracksite is one of only three known hominin tracksites dating from the age during which modern human behaviour emerged. (All three of these sites have been found in South Africa, which is consistent with the latest thinking regarding the origins of modern human behaviour);

- Knysna’s hominin tracksite is the largest known and best-preserved archive of human tracks from the Late Pleistocene;

- The fact that ‘our’ human tracks occur at this site in association with tracks from other species helps us understand coastal dune palaeoecology during the Late Pleistocene.

Research

* A New Pleistocene Hominin Tracksite from the Cape South Coast, South Africa was published by nature.com on 28 February, 2018. Authors:

- Charles W. Helm (senior author) of Canada’sPeace Region Palaeontology Research Centre, and theAfrican Centre for Coastal Palaeoscience at Nelson Mandela University, Port Elizabeth;

- Richard T. McCrea of the Peace Region Palaeontology Research Centre;

- Hayley C. Cawthra of the African Centre for Coastal Palaeoscience, and the Marine Geoscience Unit of the South African Council for Geoscience;

- Martin G. Lockley of the Dinosaur Trackers Research Group at the University of Colorado Denver, USA;

- Richard M. Cowling of the African Centre for Coastal Palaeoscience;

- Curtis W. Marean of the African Centre for Coastal Palaeoscience, and the Institute of Human Origins, School of Human Evolution and Social Change, Arizona State University, USA;

- Guy H. H. Thesen of the African Centre for Coastal Palaeoscience;

- Tammy S. Pigeon of the Peace Region Palaeontology Research Centre; and

- Sinèad Hattingh of the South African Spelaeological Association

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Dr. Helm: [email protected]

** Footprint Clues in Hominid Evolution and Forensics: Lessons and Limitations by Russell H. Tuttle, Professor of Anthropology, Evolutionary Biology, History of Science and Medicine at the University of Chicago, published in the journal Ichnos, an International Journal for Plant and Animal Traces, Volume 15, 2008, Issue 3-4

*** Pleistocene large reptile tracks and probable swim traces on South Africa’s Cape south coast by Charles W. Helm, Hayley C. Cawthra, Xander Combrink, Carina J.Z. Helm, Renée Rust, Willo Stear, and Alex van den Heever, published in the South African Journal of Science, 26 March, 2020

Visit the African Centre for Coastal Palaeoscience

- This article in the series, Our Heritage in Stone, was written for knysnamuseums.co.za by Martin Hatchuel, Charles W. Helm, and Fred van Berkel (geologist, retd.). Published 20 May, 2020

Update (1): More track sites discovered

A new paper published after this article was written describes a number of 'new' track sites in the Southern Cape. Please see:

Charles W. Helm, Martin G. Lockley, Hayley C. Cawthra, Jan C. De Vynck, Mark G. Dixon, Carina J.Z. Helm, Guy H.H. Thesen: Newly identified hominin trackways from the Cape south coast of South Africa - South African Journal of Science, Volume 116 No. 9/10 (2020) - 29 September, 2020

ABSTRACT: Three new Pleistocene hominin tracksites have been identified on the Cape south coast of South Africa, one in the Garden Route National Park and two in the Goukamma Nature Reserve, probably dating to Marine Isotope Stage 5. As a result, southern Africa now boasts six hominin tracksites, which are collectively the oldest sites in the world that are attributed to Homo sapiens. The tracks were registered on dune surfaces, now preserved in aeolianites. Tracks of varying size were present at two sites, indicating the presence of more than one trackmaker, and raising the possibility of family groups. A total of 18 and 32 tracks were recorded at these two sites, respectively. Ammoglyphs were present at one site. Although track quality was not optimal, and large aeolianite surface exposures are rare in the region, these sites prove the capacity of coastal aeolianites to yield such discoveries, and they contribute to what remains a sparse global hominin track record. It is evident that hominin tracks are more common in southern Africa than was previously supposed.

Significance:

- Three new Pleistocene hominin trackways have been identified on the Cape south coast, bringing the number of known fossil hominin tracksites in southern Africa to six.

- The tracks were all registered on dune surfaces, now preserved as aeolianites.

- These are the six oldest tracksites in the world that are attributed to Homo sapiens.

- Hominin tracks are more common in southern Africa than was previously supposed.

Update (2) April 2021: Ammoglyphs

In, ‘Patterns in the sand: A pleistocene hominin signature along the South African coastline?’ in Proceedings of the Geologists' Association, Volume 130, Issue 6, 2019, Charles Helm, Hayley Cawthra, Jan De Vynck, Carina Helm, Renee Rust, and Willo Stear, described fossilised marks in aeolianite deposits that might be attributable to hominins who lived on Cape South coast.

And in, ‘What triangular patterns on rocks may reveal about human ancestors’ (The Conversation, April 25, 2021), Charles Helm writes, ‘The patterns that we have found consisted of circles, grooves, “hashtags”, fan shapes and even what appeared to be a sand sculpture that resembled a sting-ray. In our research paper about these discoveries, we introduced the term “ammoglyph” to describe a pattern created by humans in sand that is now evident in rock.’

Share This Page